ETFs provide Australian investors with a simple way to construct well-rounded portfolios diversified across a wide variety of international and domestic markets. With the widespread adoption of ETFs over recent years, many investors have asked great questions about how ETFs work, and the most appropriate way to trade them. This article aims to answer some of the most common questions.

Why does it look like there aren’t many ETF units available?

The intra-day traded volume of an ETF shown on screen should not be seen as an indicator of the level of liquidity of the ETF.

ETFs are open-ended funds, which means the ETF provider can create or redeem units according to investor demand.

All ETFs have one or more designated market makers whose core responsibility is to ensure there are sufficient units in the ETF available so that investors can buy or sell when they choose to do so. Should investor demand exceed what is shown on screen, market makers can simply ‘create’ more units (issued by the ETF provider) to meet that demand, and likewise can redeem units when supply exceeds demand.

The market makers will attempt to also maintain a tight bid/ask spread (the difference between the price to buy and the price to sell units) so that the price of the ETF closely approximates the net asset value (NAV) per unit throughout the trading day.

All this helps to keep ETFs as liquid as their underlying holdings. As long as there is liquidity in the underlying holdings of an ETF, there will always be the ability for the market makers to ‘create’ more ETF units to supplement the liquidity seen on screen.

When is the best time to buy and sell ETFs?

When considering the cost of an ETF it is important that investors consider the size of the bid/ask spread as part of the cost of entering and exiting the position, when assessing the total cost of the investment, taking into account the expected investment timeframe.

Markets can be volatile, and prices can move around a lot in a short period of time. As a general rule, ETF investors should consider avoiding making a trade near market open and close. It considered prudent to avoid trading within the first 10 minutes of market open, as a combination of breaking and overnight news, economic data and market activity can lead to a period of price volatility as trading begins, with wider spreads sometimes evident. Typically, after this period the market tends to normalise.

It is also considered prudent for investors to avoid the last 10 minutes of the trading day. This period can see large volumes traded, which may increase volatility.

What are limit orders and how can they be used?

A market order is one in which an investor offers to buy or sell a given number of ETF units (or other securities) at whatever price is required to fill the order. A limit order, by contrast, has a price limit attached to it – it is an order to buy (or sell), but at no more (or less) than a specified price.

For relatively small orders in normal market conditions, the distinction between limit and market orders in practice may not make much difference. But in times of market volatility, the difference between these types of orders can matter greatly.

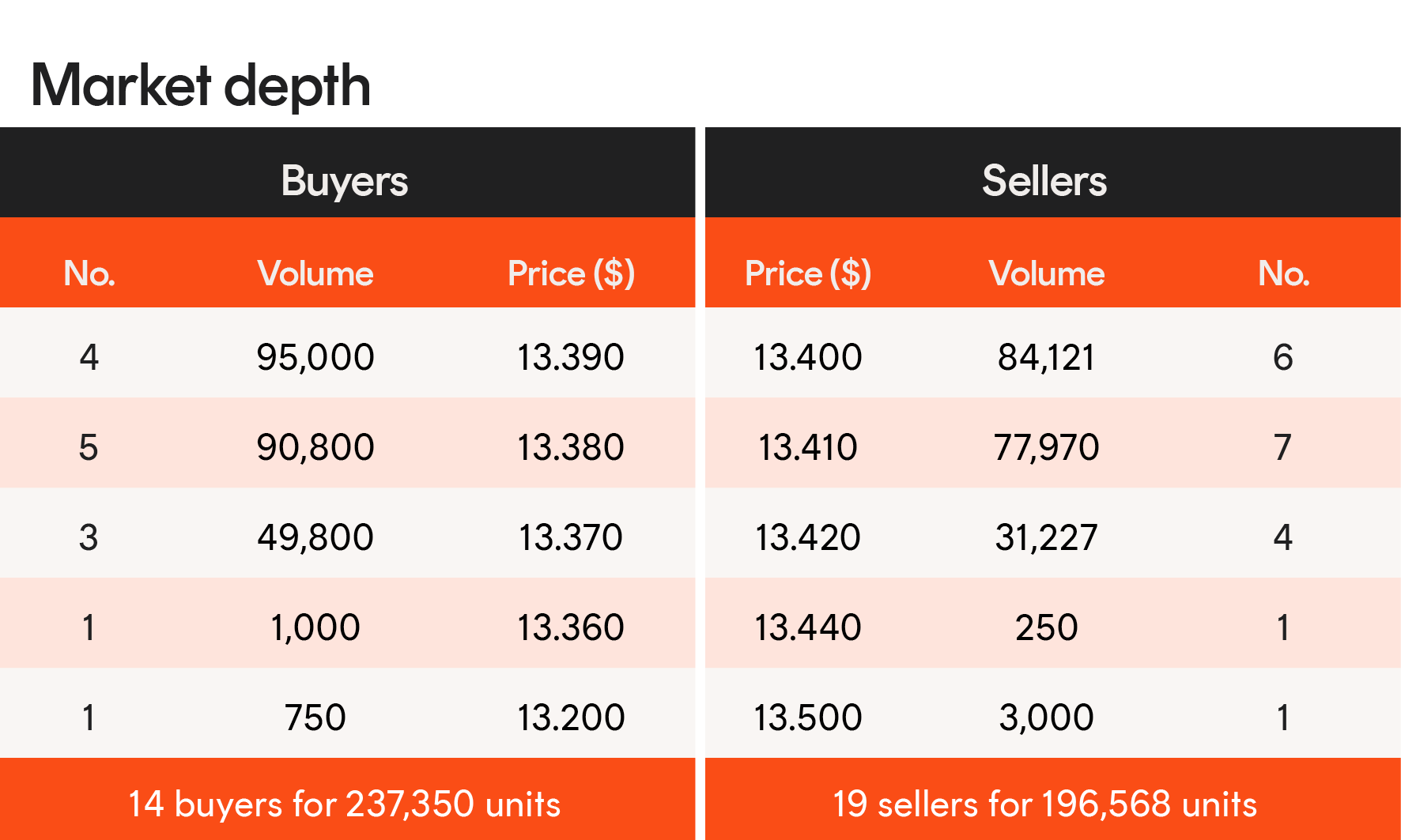

QOZ market depth Source: Betashares. Example provided for illustrative purposes only, it is not a recommendation to make any investment decision or adopt any investment strategy.

Source: Betashares. Example provided for illustrative purposes only, it is not a recommendation to make any investment decision or adopt any investment strategy.

In the example above, an investor wishing to sell 10,000 units of QOZ could place either a limit (at $13.39) or market order – and both would likely be filled at the prevailing price of $13.39. If it were a larger sell order, however, (say for $2 million worth of units), the investor could place an order for around 150,000 units of stocks at a limit of $13.39 – and see if the market maker meets it.

But if this investor placed a market order to sell 150,000 units, they would end up selling 95,000 units at $13.39 and the remaining 55,000 units at $13.38 – a lower average price. In this particular case the overall price realised is likely to be acceptable, as there is only 1 cent between the highest and second highest bid. However, it could matter in times of market panic and volatility, when there may be many sellers at the same time, and the order may only be filled at lower prices. In such a situation, using market orders to sell units creates the risk of being filled at prices well below prevailing NAV – something which no investor wants!

Why is the Nasdaq 100 Index up 2% at close in the US, but my ASX-quoted NDQ ETF is down 1% this morning?

This is a common question around ETFs whose underlying assets are traded on overseas markets. It indicates why investors need to be careful when investing in markets in different time zones to the one in which the investor is located.

In this specific example, given NDQ is quoted on the ASX, the price of the ETF relies on overnight futures markets (that operate almost around the clock) to provide an accurate level of pricing, given that the US market, in this case the Nasdaq-100, is closed during ASX trading hours.

Given this, the question comes down to after hours trading both here and in the US, where futures pricing will reflect after-market announcements, and economic sentiment from other global markets. The ASX-quoted NDQ will trade off futures pricing, which may differ from the closing price of the (physical) US Nasdaq index.

For answers to more commonly asked questions about ETFs, please refer to Frequently Asked Questions.

There are risks associated with an investment in the Funds, including market risk, security specific risk, sector concentration risk and in the. Investment value of units can go up and down. An investment in the Funds should only be made after considering your particular circumstances, including your tolerance for risk. For more information on risks and other features of the Funds, please see the Target Market Determination (TMD) and Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) for each of the relevant Funds, available at www.betashares.com.au.

Written by

Blair Modica