8 minutes reading time

Commentary from the Betashares portfolio management desk by Head of Fixed Income Chamath De Silva, providing an overview of bond markets:

- Elevated long-term sovereign bond yields and the steepening of global yield curves have implications that might be lost on many investors.

- Despite the growing narrative around fiscal dominance and stagflation, the value of duration is becoming increasingly attractive due to higher risk premiums.

- Long-term bonds now present a compelling opportunity to capitalise on convexity amid a rapidly deteriorating US labour market.

Long-term bonds still misbehaving

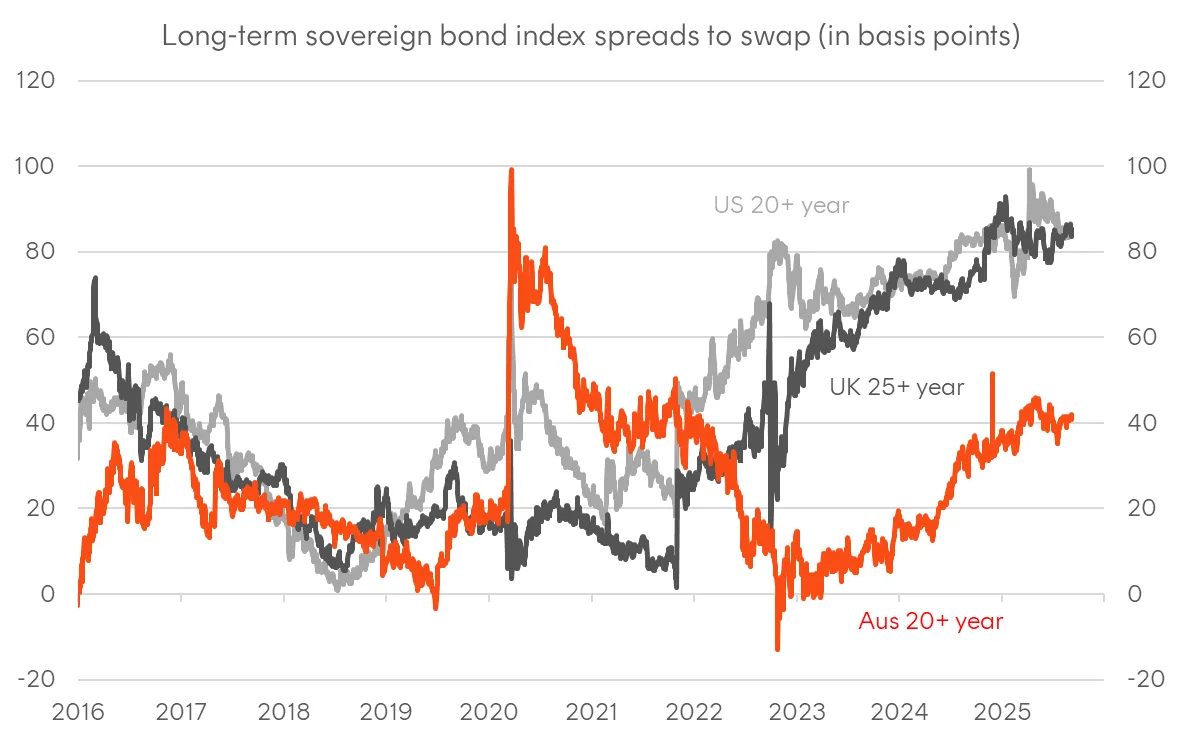

The big story of late has been the ongoing weakness in long-term sovereign bond yields and the steepening of global yield curves. This has occurred against a backdrop of the global rate cutting cycle continuing, with the Fed now clearly guiding towards a resumption of rate cuts amid a weaker labour market. Following Friday’s weaker-than-expected US jobs report, market pricing has shifting towards 3 cuts for this year, with front-end yields dropping and a terminal Fed Funds rate now below 3%. However, global long-term yields are either trending higher or drifting sideways.

Perhaps the poster child of this “bear steepening” has been the UK, with recent moves rekindling memories of September 2022 when the mini-budget roiled the gilt market, sparked a crisis in the liability-driven investing space, and forced an emergency response from the Bank of England. What’s particularly notable is that 30-year gilt yields are now much higher than even the intraday peak of 2022.

Most memorably, that episode ended the administration of then-PM Liz Truss, whose name has since become synonymous with sovereign bond volatility. In recent years, a big part of the macro debate has been whether the US will face its own “Liz Truss moment”, amid growing deficits, heightened concerns around so-called “fiscal dominance” and general “stagflationary” fears. and there’s possibly some degree of contagion that’s spilled over to even the Australian long end. This WHIB will get into the weeds of global rates and try to unpack the question of whether we should be worried about what’s happening at the ultra-long end or embrace it.

Chart 1: Selected 30-year sovereign yields; As at 5 September 2025; Source: Bloomberg

Chart 2: Terminal, neutral and long-term US yields; As at 5 September 2025; Source: Bloomberg, CME, FOMC

Easing = steepening

Firstly, it’s important to ask ourselves whether this development is unusual. Based on history and the mechanics behind bond yields, there’s no reason why 30-year yields should always fall during an easing cycle, especially if rate cuts are seen as precautionary rather than emergency in nature. The official line from several central banks, including both the Fed and RBA, is that rate cuts are largely a recalibration of their policy stance, from restrictive to neutral amid a combination of inflation pressures (generally) moderating and labour markets softening.

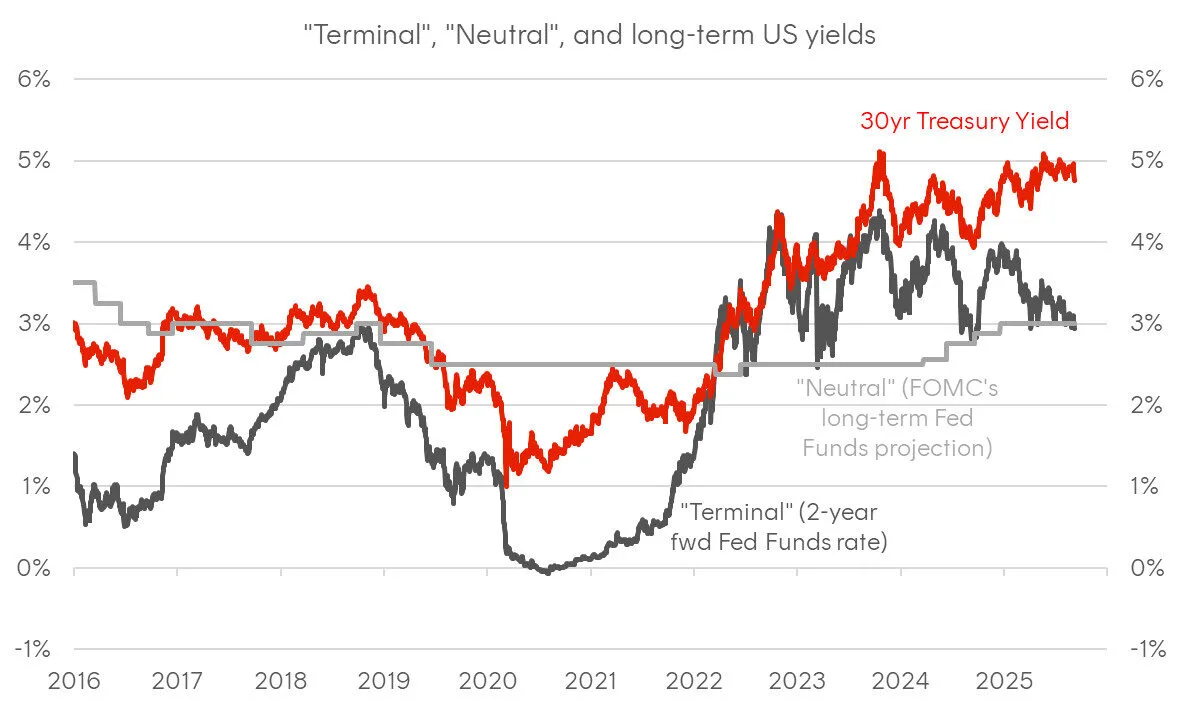

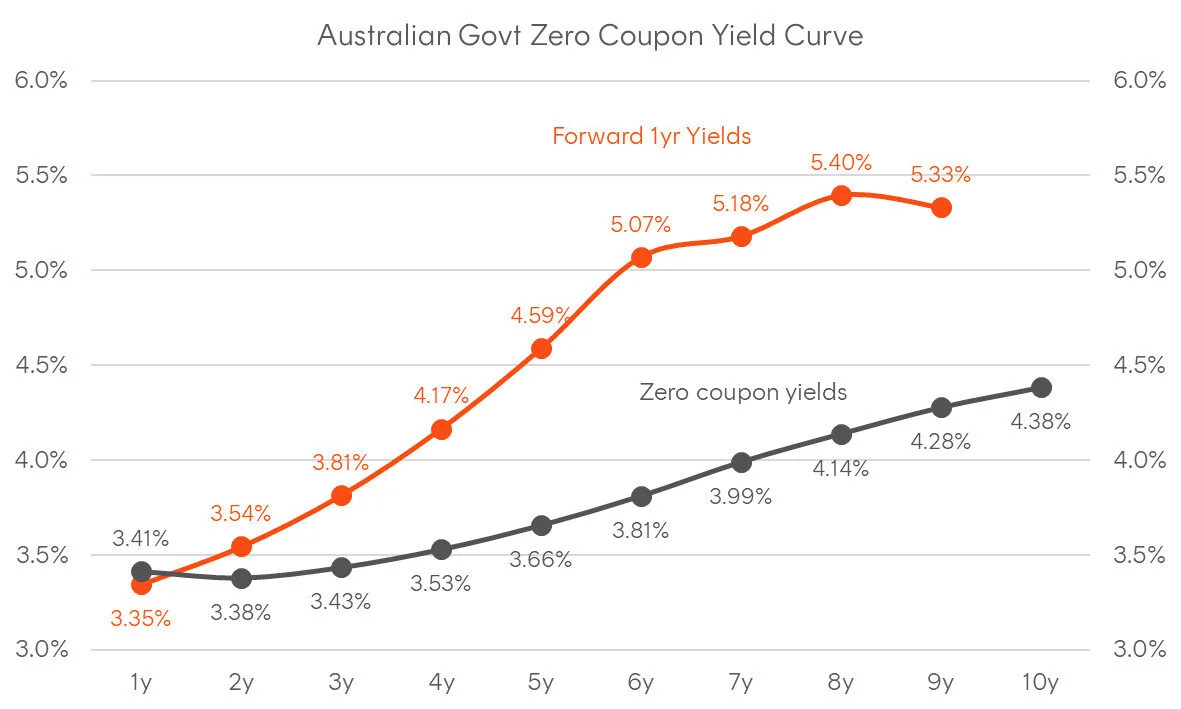

The other thing to remember is that an easing of policy should entail a steepening of the yield curve. The main reason is that long-term yields can be seen as a combination of current and future policy rate expectations, plus a term premium – the risk premium for taking on the combination of inflation risk, interest rate risk, and liquidity risk over the life of a long-term bond.

A forward yield curve – how the market’s implied forward short-term interest rate evolves with time – will be heavily influenced by policy expectations and the central bank’s reaction function over the next 1 to 2 years. However, further out in time, there are usually “neutral” levels to pin longer-term implied forward interest rates, and these levels should in theory be relatively insensitive to the current policy cycle. As a result, the forward rates curve should be upward sloping from the “terminal” level of the current cycle. In addition, if a rate cutting cycle is seen by the market as likely to succeed in easing financial conditions, it should spur nominal growth expectations, which would naturally raise expectations of a tightening cycle to eventually follow. Therefore, higher longer-term growth and inflation expectations plus a higher risk premium should naturally lead to steeper curves during rate cuts.

Chart 3: Australian government forward curve decomposition (forward 1yr yields); Ast at 5 September 2025; Source: Bloomberg

Chart 4: Australian government zero coupon and forward 1yr yield curves; As at 5 September 2025; Source: Bloomberg

Finding value in global duration

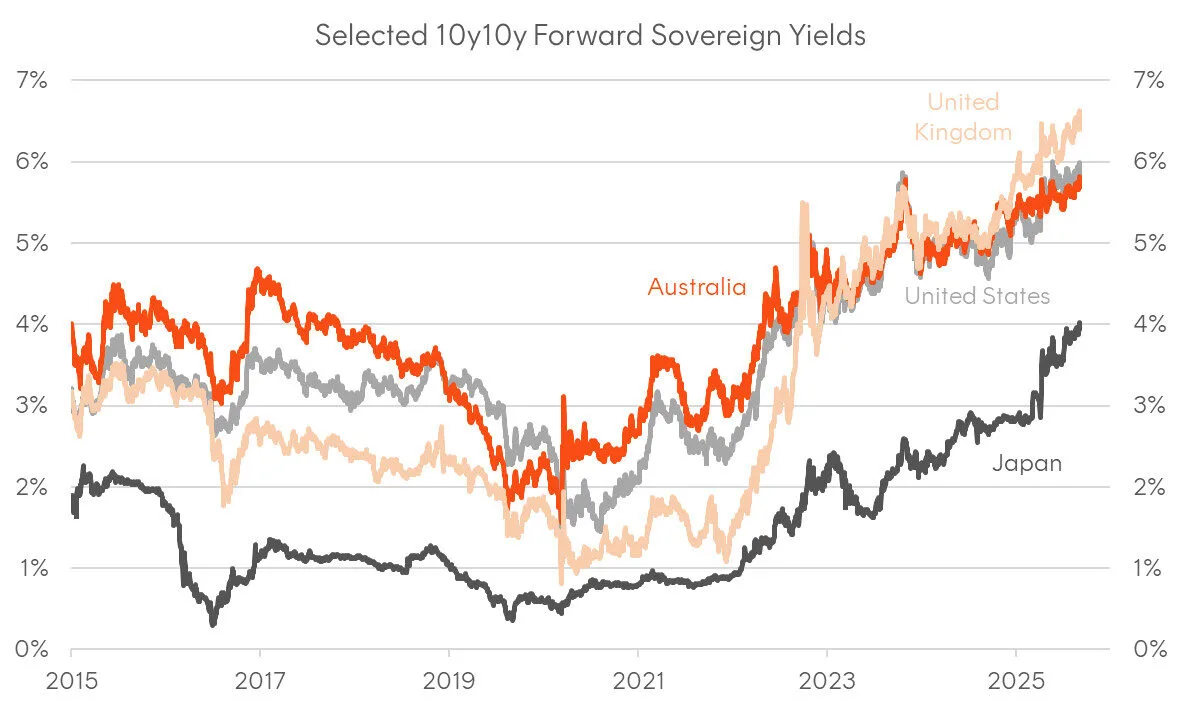

Although a steepening should be expected during rate cuts, there’s decent evidence to suggest that the actual relative value of long-duration bonds has become much more compelling, increasingly reflecting more a risk premium than pure long-term neutral policy rates. I won’t focus on the academic estimations of the term premium but instead look at observable market-based measures, such as 10y10y forward yields, and long-dated swap spreads (or asset swap spreads), the latter of which reflects the pure yield spread that government bonds are paying above the swap curve.

10y10y forward yields are basically the market’s pricing on long-term yields over the long-term, and right now they’re at multi-decade highs for the US and UK. These capture both the current levels of long-term yields and the steepness of the yield curve, and this measure for US Treasuries is around 6%, while for UK gilts it’s 6.5%. The Australian equivalent has also been dragged higher to decade highs of around 5.7%. The best way of interpreting this is either neutral policy rates are much, much higher than most economists and central bankers believe, or that the risk premium for duration is very attractive.

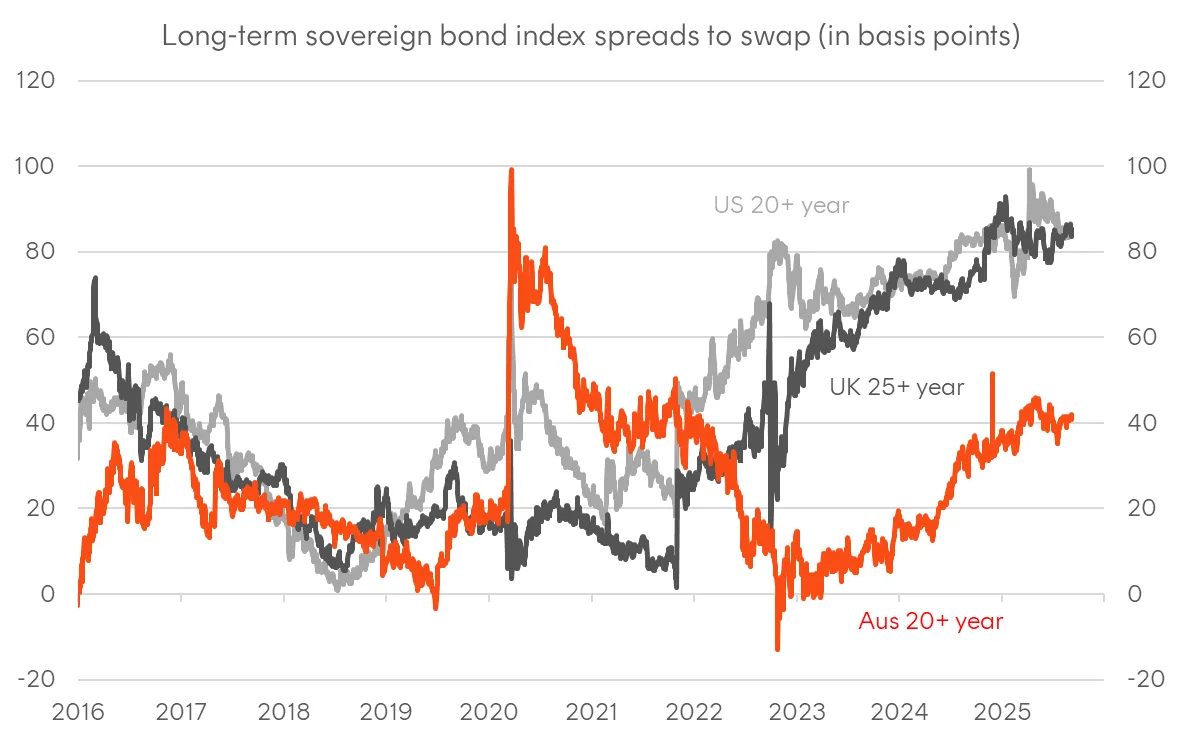

Asset swap spreads allow us to reflect sovereign bond pricing in terms of a yield spread over the synthetic risk-free swaps curve, the fixed-rate equivalent to the discount margin for floating rate notes. In the post-GFC era of central clearing, interest rate swaps are effectively considered risk-free, so any yield spread Australian commonwealth bonds, US Treasuries or UK gilts pay over swap is pure risk premium for either credit risk (which we can assume is zero) or liquidity risk, with the latter also reflecting issuance indigestion. Asset swap spreads on long-term sovereign bonds have been trending higher, led by the UK and US, and Australian ultra long-term bonds (20-30 year) are now offering quite a compelling pickup over AUD swap, although not to the degree of US Treasuries or gilts.

Ultra long-dated sovereign bonds are possibly the most hated part of the market right now, and the narrative of an erosion of central bank independence, fiscal dominance, and a willingness to run economies hot amid structural growth challenges isn’t helping. However, market pricing is presenting a hurdle that’s getting easier to clear for long-term investors. Long-term bonds don’t always provide portfolio insurance, and much of what drives stock-bond correlations is the inflation regime. However, the worst episodes for the global economy, credit markets, and risk assets more generally have coincided with inflation expectations plummeting. Outperformance from ultra long-term government bonds during such episodes is a function of both the emergency policy response, the flight to quality from risk assets, and the “convexity”, which is increasingly being ignored.

Friday’s poor payrolls data – with job growth grinding to a halt and unemployment rising to new cycle highs – provided a timely reminder of how quickly the narrative can shift. Long-term Treasuries rallied sharply as markets scrambled to price in a more aggressive Fed easing cycle, with the Bloomberg 20+ year index ending the session up 1.5%. This type of dramatic repricing is what makes the convexity in long-duration bonds so valuable. Convexity produces asymmetric upside versus downside for a given change in yields, giving it insurance-like properties, and it’s arguably cheaper than it’s been in a long time.

Chart 5: Selected 10y10y forward sovereign bond yields; Source: Bloomberg

Chart 6: Long-term sovereign bond index spreads vs local currency swap; as at 5 September 2025; Source: Bloomberg