5 minutes reading time

The AI-driven rally in equity markets – led by the largest US technology companies – has fuelled debate about whether we are entering a bubble. Historically, bubbles arise from investor exuberance around transformative technologies, leading to surging capital flows and valuations far beyond fundamentals. Some aspects of today’s environment rhyme with past episodes but important differences do stand out.

Today’s leaders are supported by robust earnings, strong balance sheets and proven business models, rather than speculation. Share buybacks and dividends – which were absent during the Dot-com boom – are now commonplace. Assessing current fundamentals, valuation levels and the still-untapped AI monetisation opportunity suggest today’s market environment lacks the excesses seen in prior bubbles.

Earnings power, not hype

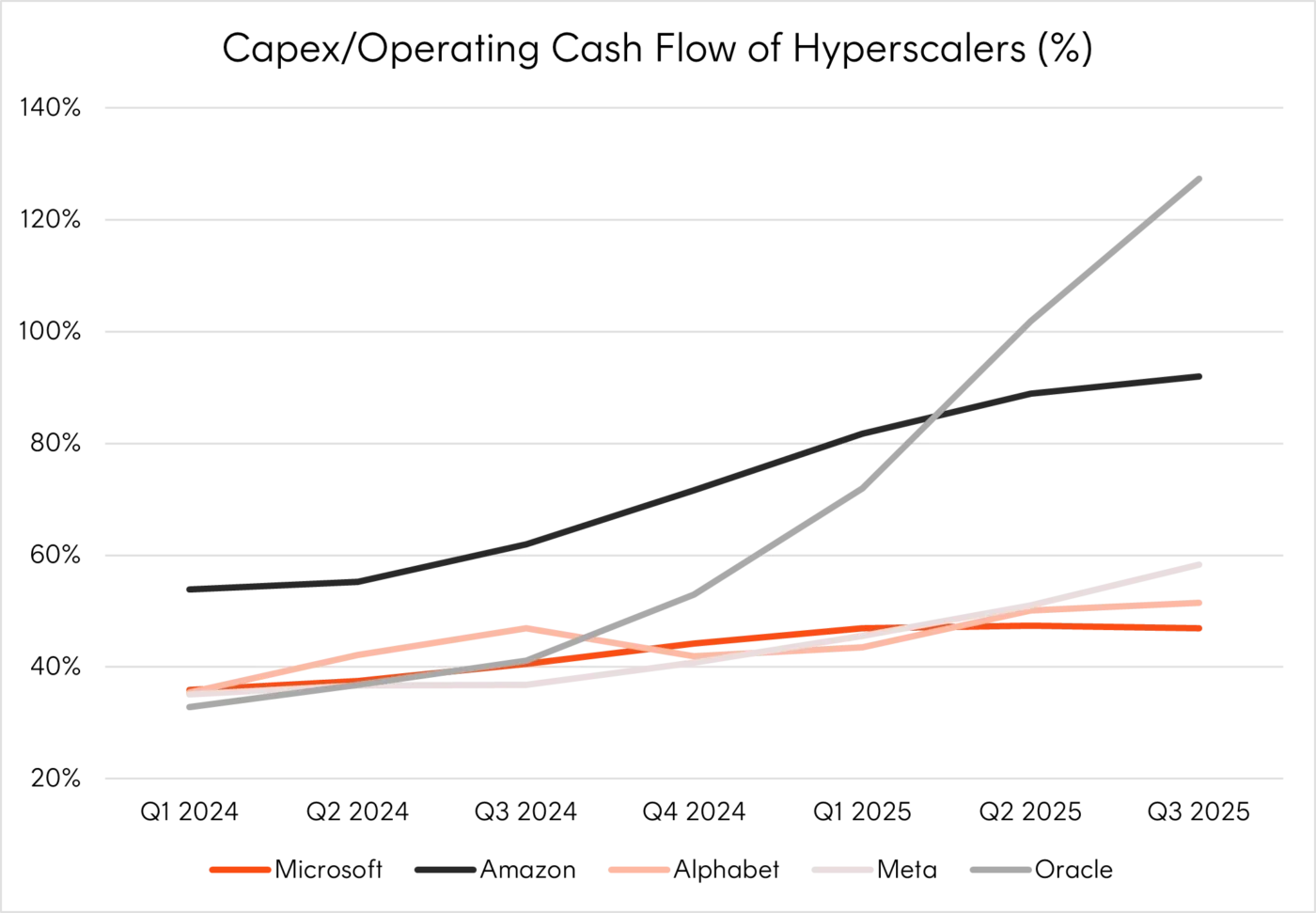

The “Magnificent 7” have earned their leadership through consistent profit growth, pricing power, and reinvestment into future initiatives. Collectively, they generated more than US$200 billion of free cash flow in the last year. While debt issuance has risen, most AI-related capex is funded by operating cash flows (Oracle being the key exception) which is underpinning much of their market leadership, rather than speculative capital.

Source: Nasdaq Global Indexes, Bloomberg. As at November 2025.

With these strong fundamentals, the US hyperscalers now make up 27% of the S&P 500 and are worth a combined US$21 trillion—larger than many national economies. While this has led to high concentration among just a few names, we think this instead reflects the market leadership position that the US megacap tech companies have established over the past decade.

Compare that to the more worrying type of concentration seen in past bubbles which involved low-quality companies gaining capital despite having unproven business models.

Valuations: elevated, but not 2000-style extremes

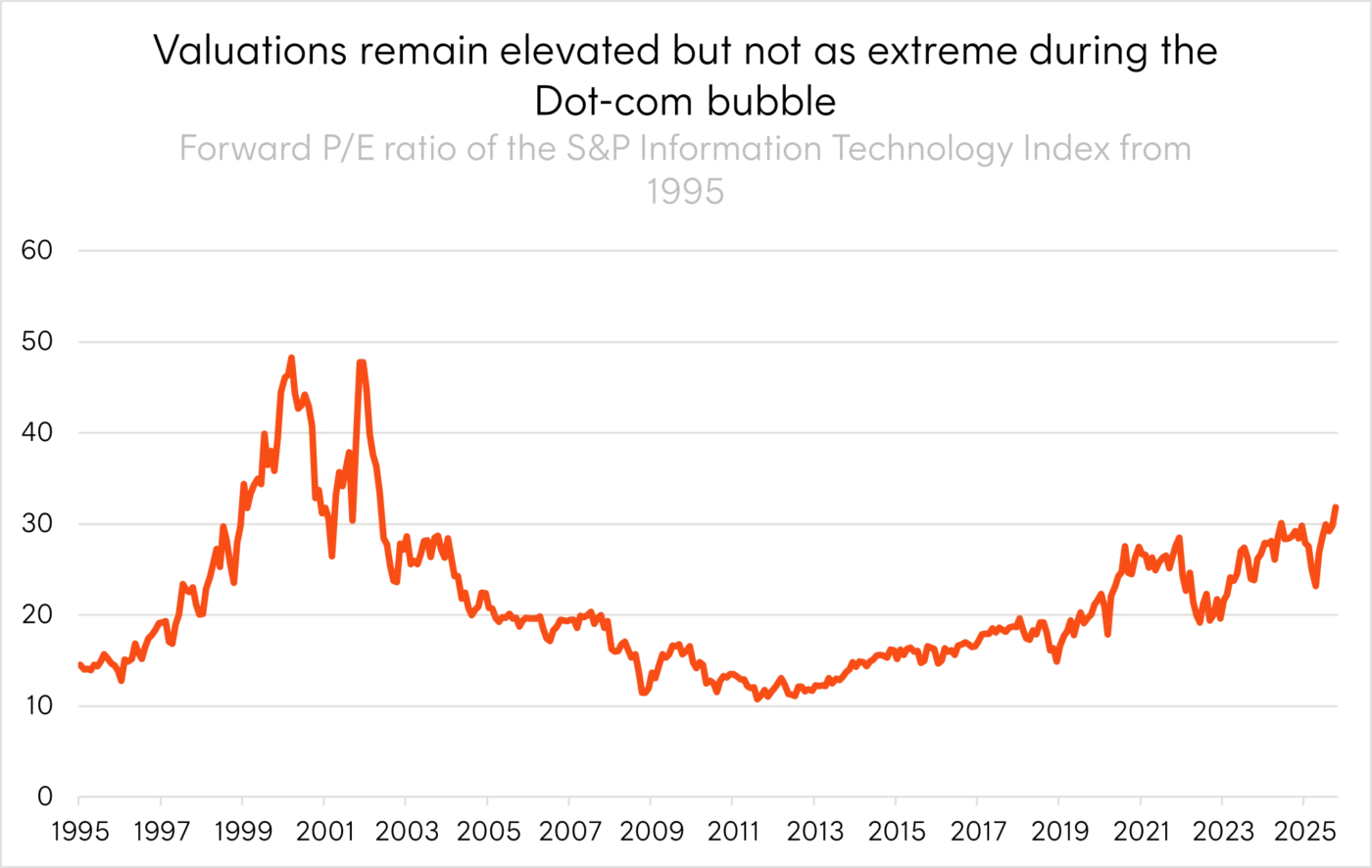

Valuations can often provide a barometer for investors as to how expensive or inexpensive a particular index or stock is.

The chart below shows that at current levels; we are far from Dot-com levels. The S&P Information Technology Index trades on a forward P/E of roughly 30x—around 1.5 standard deviations above its long-term average, but well below the near-50x multiple seen during the March 2000 peak.

Source: Datastream. As at 25 November 2025.

On an absolute basis, one might conclude that valuations still feel rich. But when judged using the PEG ratio (price to earnings growth), the sector looks ‘fairly priced’. The current PEG ratio of ~1.12x suggests today’s multiples are more aligned with expected growth than during Dot-com excess. However, this metric is only as reliable as the growth forecasts behind it, and analyst estimates may prove too optimistic.

That said, we think the most compelling difference versus the late 1990s is that the market’s advance over the last three years (since the launch of ChatGPT in late November 2022) has been driven mostly by earnings growth, not multiple expansion.

What about the massive amounts of AI spending?

Another concern among investors is that the enormous capex outlays for AI infrastructure are not yet translating into meaningful revenue. Hyperscalers are expected to spend over US$530 billion next year on AI-related investments, with only a small portion monetised today.

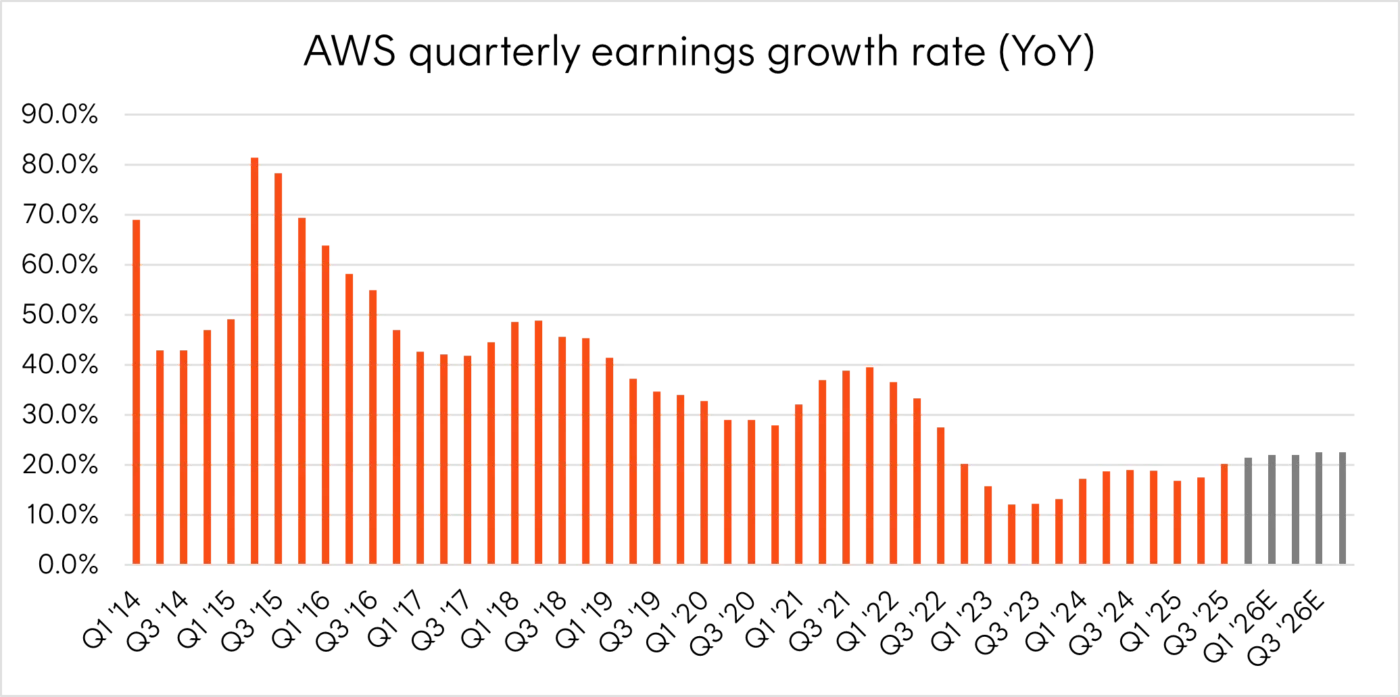

Yet this pattern is typical of breakthrough technologies. Cloud computing and mobile broadband both required years of upfront spending before revenue scaled. Only after the iPhone’s launch in 2007 did smartphone demand take off—ultimately generating value far beyond the cost of building 3G/4G networks. Likewise, cloud revenue acceleration lagged the 2010–15 capex buildout by several years before becoming the fastest-growing and highly profitable business units inside Amazon, Microsoft, and Google.

Today, Amazon Web Services accounts for ~15% of Amazon’s revenue but delivers ~60% of total operating income—a vivid demonstration of the payoffs once scale is reached.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. Growth rates from Q4’ 25 onwards are estimates, highlighted in grey.

Looking forward, we think monetisation will increasingly shift from training models to inference (the process of producing outputs such as chatbot answers, summaries or even code) as enterprises deploy AI into workflows. With every inference event, AI platforms are able to monetise usage that scales accordingly with end-user demand, creating attractive unit economics.

The development of automated AI agents will also amplify this effect: a single task from an agent may create dozens or even hundreds of inference steps, driving recurring, high-margin revenue opportunities. Amazon is already releasing autonomous software-development agents, with the Commonwealth Bank of Australia among the early adopters.

And as hardware becomes more efficient and inference costs decline over time, new use cases become viable, driving even more activity and accelerating the enterprise AI adoption S-curve.

Boom, bubble, or something in between?

Certain aspects of the current market echo earlier bubbles: lofty valuations, heavy front-loaded capex and questions around payback. But unlike prior cycles, the primary drivers today are fundamentals – profitability, market demand and monetisable technology – rather than cheap money or retail speculation.

Investors may be hesitant to pay for earnings that are still several years away, given uncertainty in timing. Those seeking rapid returns may be frustrated. But investors who stay patient through the steepest phase of the adoption curve may be rewarded as the benefits compound.

Overall, we think AI is a once-in-a-generation platform shift with the potential to reshape industries and boost productivity-led economic growth. And with strong national-level backing in the U.S., the push to scale AI is only accelerating.