6 minutes reading time

Week in review

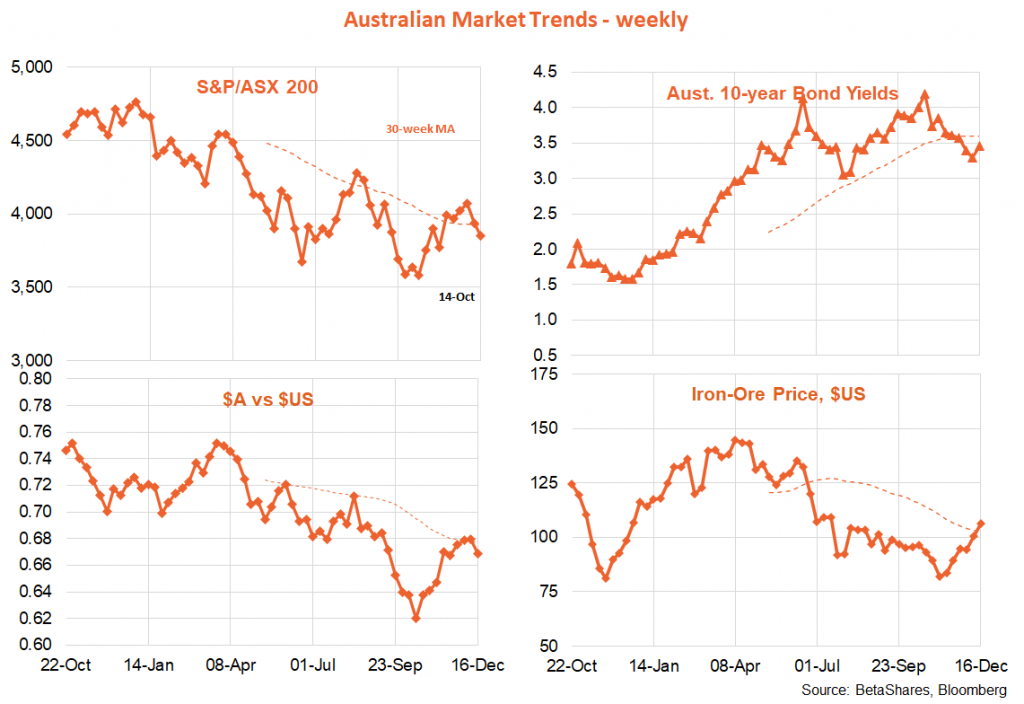

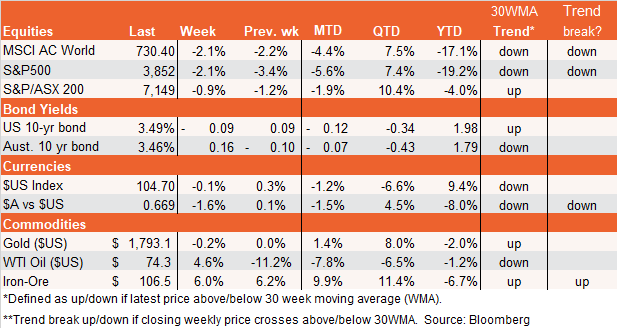

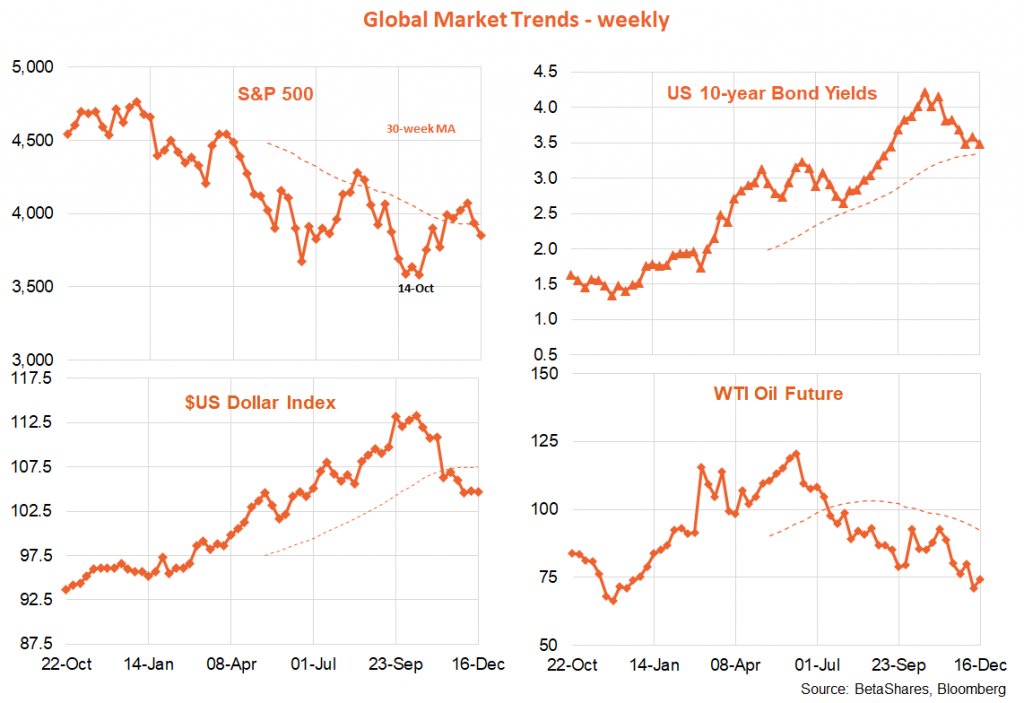

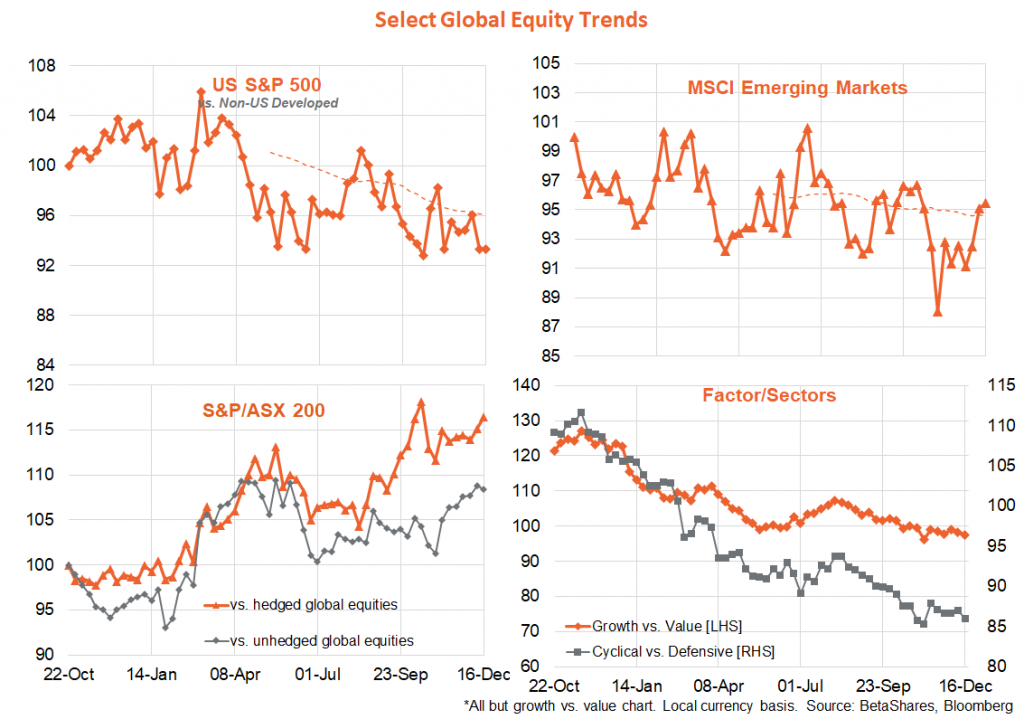

Despite a lower than expected US consumer price index (CPI) result, global equities fell back for the second week in a row due to continued hawkish sentiment from global central banks. The pullback in equities has been associated with a levelling out in US bond yields and the US dollar after declines since mid-October. In short, the Fed has spoilt the Fed pivot party once again.

First the good news! The US core CPI rose only 0.2% in November, or just under the 0.3% market expectation. As noted last week, such was the market’s sensitivity to the result, it was enough to send Wall Street soaring in the early hours of trading that day. While core goods prices continued to decline, as widely expected, there was also an encouraging slowing in core service sector inflation, with smaller monthly gains in both housing and non-housing services.

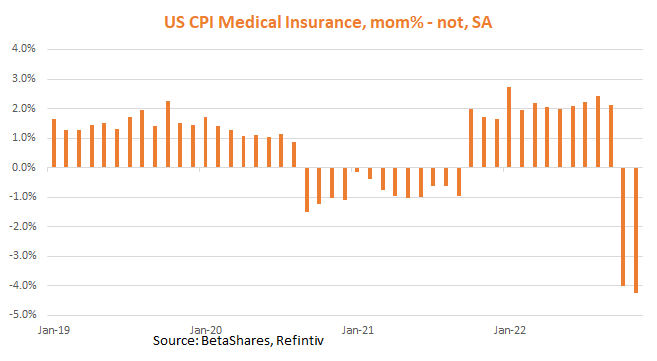

One notable but odd new development is that medical care services declined by 0.7% after a 0.6% decline in October. What gives? It turns out that this largely reflects an estimated decline in medical insurance costs, which are calculated annually and based on changes in health insurer profits in the previous year (if profits are down the US statistics boffins assume ‘quality’ of services provided from insurance premiums must have improved, leading to a decline in quality-adjusted health insurance prices). With a post-COVID rebound in use of medical services, health insurer profits have dropped after surging during COVID when people still paid insurance but could not use as many services.

As seen in the chart below, this means medical insurance costs are now assumed to fall by around 4% each month until September next year – after having been assumed to have increased by 2% per month in the previous 12 months. Medical insurance accounts for 13% of medical services and around 1% of the core CPI – so the 6% swing in their price direction is now detracting 0.06% of the monthly core CPI compared to before September. That may seem small, but when markets are sweating at even a 0.1% decline in monthly price growth, every little bit counts!

Either way, any rejoicing at the CPI proved short-lived as the Fed threw cold water over the party one day later. Although the Fed did downshift to a 0.5% rate hike (taking the Fed funds rate to a 4.25-4.5% range) as widely expected, it raised its projected end-2023 Fed funds rate range to 5-5.25% – implying another 0.75% of rate hikes next year. It also bumped up its expected end-2023 unemployment rate from 4.4% to 4.6% – implying a 1.1% rise from its recent low of 3.5%. Historically, note the US unemployment rate has never increased by more than 0.5% without triggering a recession – and once triggered, the increase in unemployment has never been contained to less than a 1% increase.

Reading through Fed chair Powell’s post-meeting commentary it’s clear that – despite declining goods prices and hoped for eventual decline in housing costs – the Fed does not think a sustainable decease in inflation back towards target is possible without also a decent slowing in wages growth, which in turn will likely require some softening in the labour market. The Fed is gunning for a decline in still strong labour demand. It hopes this can be achieved without much decline in the overall level of employment (i.e. merely the level of excess demand slows back towards available supply), but won’t be deterred if job losses are collateral damage in the quest to get wage growth down.

In short, equity markets really have nowhere to hide – if growth remains strong, the Fed will likely hike by more until it slows. And once the economy does slow, it won’t take much to trigger a recession and a decent decline in corporate earnings. That said, what does seem increasingly likely is that the Fed will downshift further to 0.25% rate increases next year – implying it may take until the third Fed meeting (in May) before the Fed stops raising rates.

As if that were not enough, the European Central Bank (and the Bank of England to a lesser degree) further soured market sentiment on Friday by jacking up rates by 0.5% and retaining their hawkish commentary.

In Australia, meanwhile, local data last week still broadly depicted a resilient economy, albeit with perhaps darkening clouds on the horizon. The good news was another strong 64k gain in employment, with the unemployment rate holding steady at 3.4% – along with only a small dip in the NAB measure of business conditions, which remain at robust above-average levels. That said, NAB’s business confidence index slipped further and is at moderately below-average levels, while the Westpac measure of consumer confidence bounced a little but remains at well below long-run average levels.

Week ahead

After last week’s excitement, there’s little for global markets to get to worked up about this week. In the US, there is a smattering of housing data which are expected to show this key cyclical interest-rate sensitive sector remains under severe pressure. US consumer confidence might bounce a little mid-week due to lower petrol prices, though the market might focus on any further deterioration in consumer expectations.

In Australia, minutes to the latest RBA policy meeting will be of some interest on Tuesday to the extent they shed any light on whether the Bank will pause hiking rates in February. That said, the minutes won’t reflect last week’s very strong labour market report.

Have a great week! Wishing you all a great festive season and see you in the new year!