Charts of the month: March 2025

7 minutes reading time

The key economic development of 2022 was the persistence of high inflation, which ultimately forced many global banks to raise interest rates aggressively. This naturally led to weakness in bond markets, but also weakness in equities as downward pressure on valuations more than offset ongoing earnings growth.

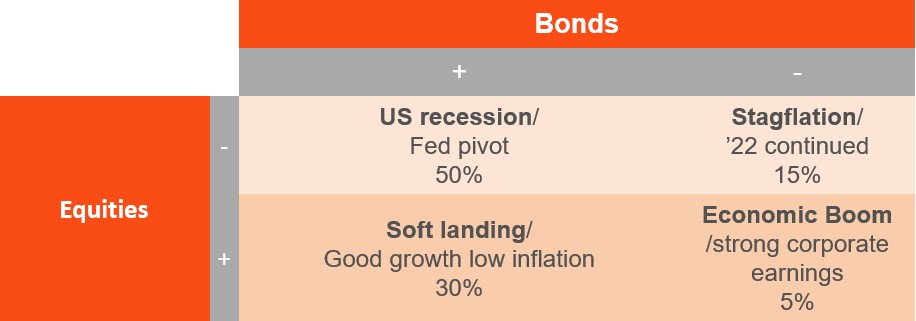

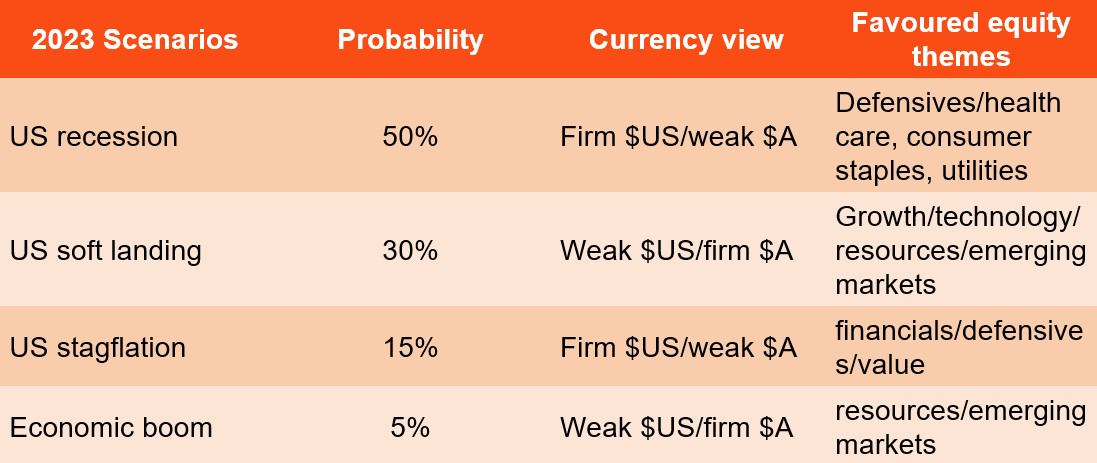

As seen in the diagram below, we attach a broadly 15% chance of such ‘stagflationary’ conditions continuing into 2023. These conditions are likely to persist if global economic growth – and especially inflation – remains firm, thereby requiring significant further central bank policy tightening and more downward pressure on both bond and equity returns. In terms of the big three asset classes, cash would remain king.

This scenario is possible if it ends up taking significant further monetary policy tightening to eventually slow global economic growth and inflation – perhaps due to lingering post-pandemic pent-up consumer demand.

Bonds and Equities: Scenarios for 2023

Economic Scenarios for 2023

By contrast, our most likely scenario (50% probability) is that the lagged impact of policy tightening over the past year, along with further modest tightening in H1’23 (largely already priced into bond markets), soon leads to a notable slowing in global economic growth, such that the US in particular descends into outright recession.

Indeed, as the world’s leading economy and major financial centre, the US economic outlook continues to dominate the broader outlook for global financial markets. Whether Europe falls into recession or China successfully re-opens its economy will affect overall global asset returns at the margin, but it’s the US outlook that remains paramount.

In this regard, several indicators already point in the direction of a US recession, such as low business and consumer confidence and inverted yield curves. Having been buoyed by ample policy stimulus during the pandemic, the US household saving ratio has also already dropped to a relatively low historic level – suggesting a depletion in ‘savings buffers’ and reduced capacity for strong spending.

In such a recession scenario, equity markets would likely fall somewhat further – at least over the first half of 2023 – though bond returns should improve on their sub-par 2022 performance.

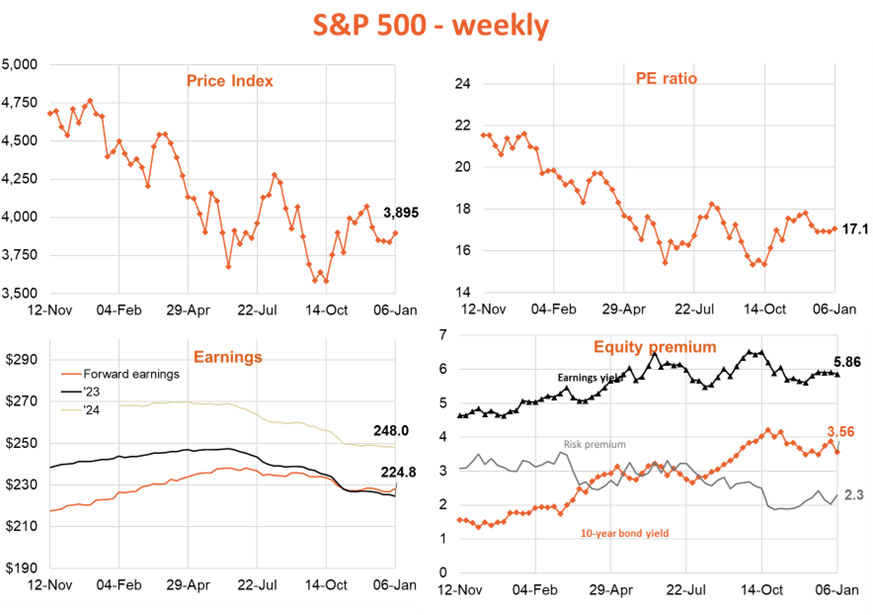

Indeed, a US recession does not appear priced into equity markets. At present, analysts still expect modest positive US corporate earnings growth of around 3% in 2023, and the S&P 500 is still trading at a relatively lofty 17 times forward earnings. In a recession, earnings in 2023 could easily fall 10 to 20%, and the PE ratio might bottom in a range somewhere between 10 and 14 times forward earnings.

Source: Refinitiv.

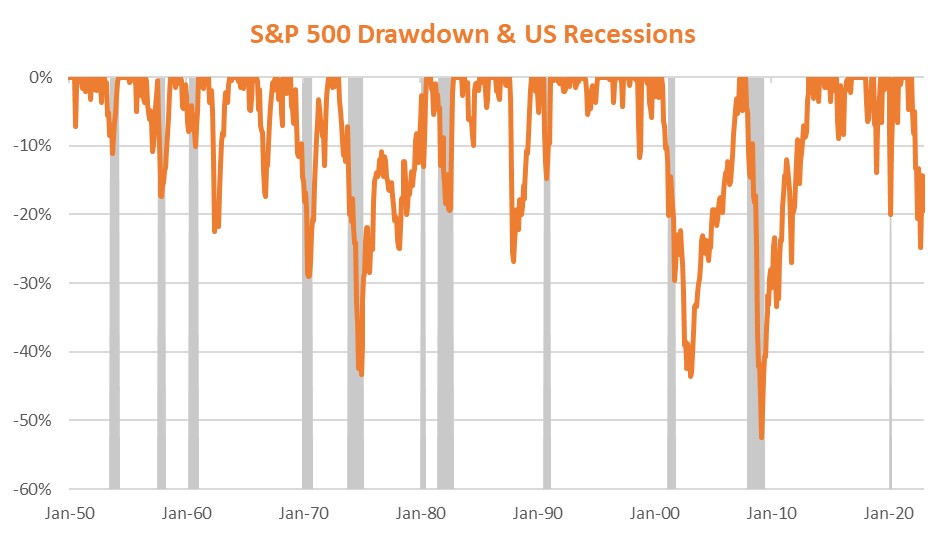

Note, moreover, US equities tend not to bottom before a US recession has even begun. The average equity decline associated with recessions is around 35%.

Source: Refinitiv. Chart depicts % decline in the US S&P 500 index from peak end-month levels. Grey areas are National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) defined recession periods.

That said, one upside risk for both equities and bonds is a ‘soft landing’ scenario, whereby inflation falls relatively quickly without first requiring a significant economic slowdown.

We give this a considerable 30% probability.

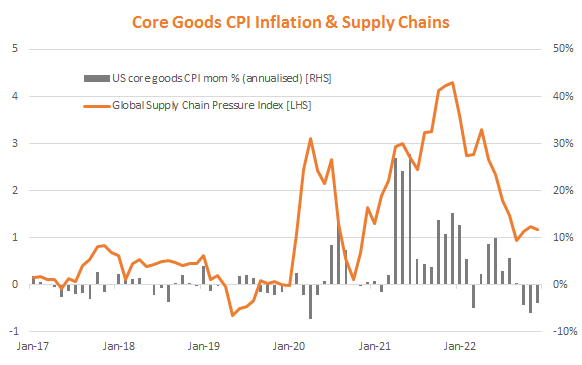

In the US, for example, goods inflation is already falling rapidly due to easing supply chain pressures and a fall back in the pandemic-related surge in goods demand. Due to the weakening housing sector, a decline in housing service inflation (largely rents) may not be far behind.

Source: Refinitiv, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

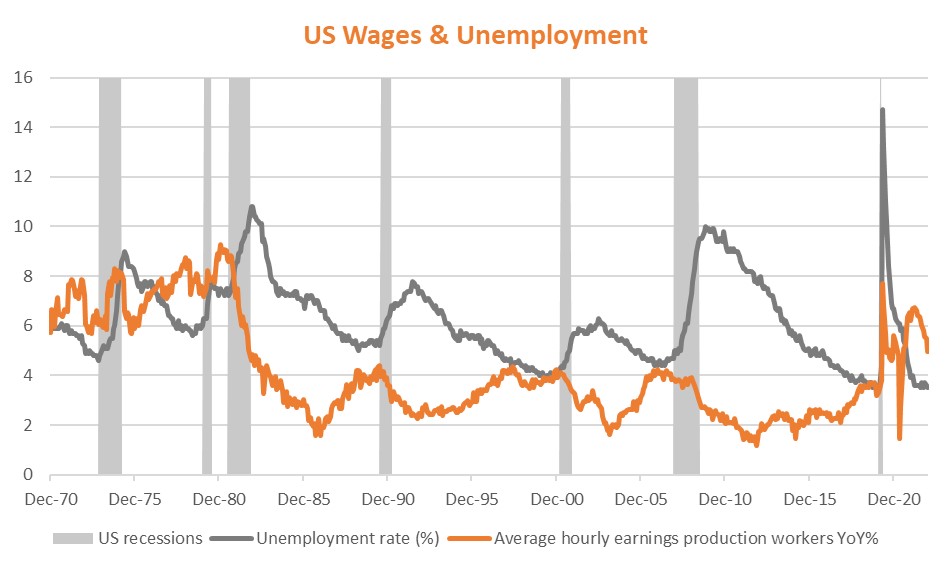

That leaves non-housing service inflation, which is largely driven by wage costs. History suggests it will take a rise in the current very low level of US unemployment to materially slow wages growth – hence our higher probability of an eventual US recession. But it’s possible that merely a decline in the current very high excess demand for workers could slow wage pressure without also requiring a significant contraction in employment.

Source: Refinitiv.

The US December payrolls report, for example, revealed a somewhat weaker than expected 0.3% gain in average hourly earnings, which slowed annual growth in this measure of wages from 5.0% to 4.6%.

Barring a material further slowing in wage growth, however, it’s unlikely the Fed would be content with just an easing in goods and housing-related service inflation – as it would judge still-firm wage growth as inconsistent with a sustainable decline in inflation over the longer-term.

In this regard the Fed has long noted it does not want to repeat what it considers “the mistake of the 1970s” whereby interest rates were eased before inflation and wage growth had notably declined to previously low levels.

The final potential scenario is an ‘economic boom’ whereby equities push higher on the back of continued solid growth in the global economy and corporate earnings even though central banks continue to raise interest rates and push bond yields higher.

Provided corporate earnings remain strong enough, such a scenario could be positive for equities, though potentially keep bond returns under pressure. Potential catalysts for such a boom could be continued strength in US consumer spending, the re-opening of the Chinese economy as COVID-19 restrictions are phased out, and/or a speedy resolution of the Russia-Ukraine war.

We give this scenario, however, only a 5% chance – both because we see more downside than upside risks to economic growth and because in the case of the latter, the implied aggressive further central bank tightening would likely still provide challenges for equity markets due to downward pressure on valuations amid fear of an eventual economic downturn later on. In other words, economic resilience is more likely to result in continuation of the 2022 ‘stagflationary scenario’, whereby both equities and bonds remain under downward pressure.

All up, based on our scenarios, we broadly judge there is a 65% probability of equities remaining under downward pressure (due to either the recession or continued stagflation scenario), though a stronger 80% probability of bonds performing well (due to the combination of the recession and soft landing scenarios).

Currency markets and equity themes

What do these scenarios mean for other investment markets? A summary of potential implications for currencies and equity themes is provided below.

We suspect a US recession will (perhaps counter-intuitively) favour the US dollar – due to flight to safety concerns – especially against global growth currencies such as the Australian dollar. Continued relatively aggressive US policy tightening under the continued stagflation scenario also favours the US dollar (as was largely the case in 2022).

Economic Scenarios: implications for currencies and equity themes

In terms of equity themes, our highest probability US recession scenario would naturally tend to favour more defensive equity exposures, such as health care, consumer staples and utilities. The currently out-of-favour growth/technology areas, by contrast, would most benefit from our second most likely scenario – a soft landing. These areas of the market are also likely to most benefit during the recovery phase following a US recession, due to lower interest rates and improving growth prospects.

The Australian resources sector – which has done relatively well over the past year – would most benefit from the economic boom scenario, especially if led by a strong rebound in the Chinese economy. Australia’s other important sector – financials – might fare better with a continuation of the stagflation scenario, with bond yields high and the economic outlook somewhat cautious.

Summary: tread cautiously

All up, the coming year promises to be another challenging one for investors, with the precarious US economic outlook potentially the biggest driver of returns. The balance of probabilities suggests there are good prospects for improved bond returns in the coming year, though likely more near-term downside risk for equity markets. In turn, this favours more defensive equity exposures and a bias towards the US dollar over the Australian dollar.

2 comments on this

Your article ,excellent work David. Very well articulated.

No one has a crystal ball. This is a fantastic article, you made it easy to understand what is really going on. Great work