ETF distributions: frequently asked questions

5 minutes reading time

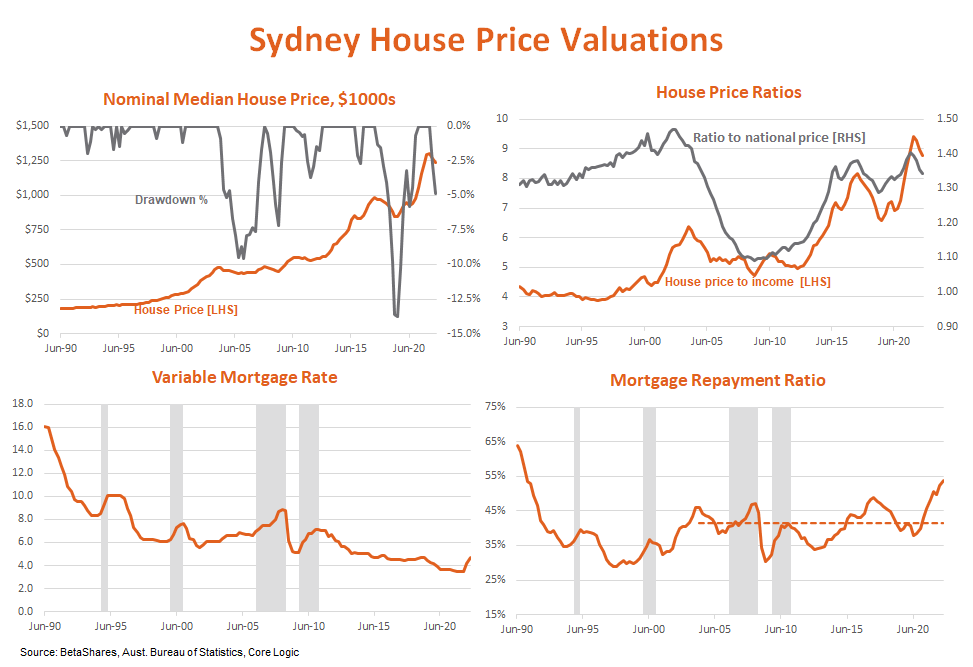

The rapid rise in interest rates so far this year following the large post-COVID rise in house prices has resulted in very stretched mortgage affordability across most capital cities. Given a likely further rise in interest rates, house prices are at risk of further downward correction – especially in the once very hot Sydney market.

BetaShares Mortgage Repayment Ratio (MRR)

The BetaShares Mortgage Repayment Ratio (MRR) aims to provide a broad indicator of the house price outlook given prevailing trends in interest rates and household incomes. It aims to estimate the percentage of after-tax income that households on an average income would need to devote to servicing a mortgage to buy a median price established home given the prevailing level of mortgage rates.

The premise behind the MRR is that over time house prices adjust to changes in interest rates and income so as to move the MRR back towards long-run average levels. If interest rates are cut, for example, resulting in a very low MRR, then house prices will tend to rise relative to income – all else constant – to push the MRR towards its average level, and vice versa.

In a blog post back in December 2020, for example, our MRR estimates suggested that “the last time our national mortgage affordability estimate was better than this was in March 2002. In the following two years, national house prices rose 36%.” We noted house prices could rise by 25% if the MRR rose back to its average since 2004, and by 35% to push the MRR back to its two previous cyclical peaks in 2010 and 2017.

As it turned out, national house prices did indeed rise by 35% from their low in the June quarter of 2020 to their recent March quarter 2022 peak.

Mortgage affordability is now stretched

Today, however, the mortgage affordability outlook is decidedly different from late 2020.

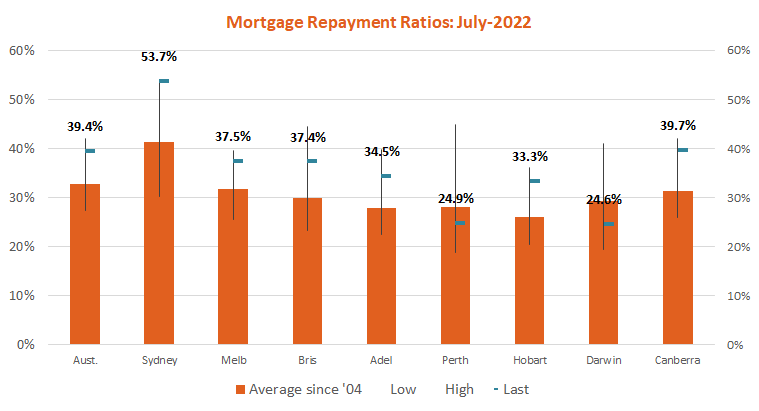

As at July 2022, the nationwide MRR has reached 39%, compared to an average since 2004 of 32.7% – and a peak level of 42% in June 2008. Our estimates suggest that if the RBA raised the official cash rate a further 1.65% – to the 3.5% expected by the market in mid-2023 – the nation-wide MRR would reach 46.3%, or well beyond its mid-2008 level (assuming the variable mortgage rate also rose a further 1.65% to 6.35%).

In fact, an RBA cash rate of 3.5% implies nationwide MRR would reach its highest levels since mortgage rates touched 16% in June 1990 (a time when the MRR hit 47.1% of income).

As also evident in the chart below, the two recent periods of rising interest rates which pushed the MRR to above average levels – in 2008 and 2012 – were associated with subsequent national house price declines of around 5%. The more recent pre-COVID macro-prudential tightening in housing credit was associated with a 9% decline in national house prices (led by a 10-14% declines in Sydney, Melbourne and Perth). So far at least, national house prices are down around 2.5% from their peak levels earlier this year, but declines of at least 10% seem more likely this time around if the RBA raises the cash rate anywhere near 3.5%.

Sydney market especially vulnerable

Due to earlier macro-prudential tightening and poor affordability, Sydney’s established housing market has already experienced double digit house price declines in past cycles – with the ABS Sydney house price index declining 13.7% in the two years to June 2019 (even without RBA interest rate increases). At the peak in Sydney house prices in June 2017, the city-based MRR had reached 49% – compared to an average since 2004 of 41.4%.

As at July, and even with a 5% decline in prices already, the Sydney MRR stood at 53.7% – a level only exceeded back in 1990! It’s fair to say the Sydney market appears vulnerable to a house price correction at least as large as the 13.7% decline in the two years to June 2019.

More generally, as evident in the chart below, all capital cities with the exception of Perth and Darwin had above average MRRs as at July 2022, making them vulnerable to nominal house price declines in the coming year as interest rates rise further. The challenge for markets nationwide will be especially acute if economic growth slows yet inflation remains stubbornly high – limiting the extent to which the RBA can come to the rescue via a ‘pivot’ towards interest rates cuts.

*Specifically, our estimates are based on the median capital city established house price (as measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics), combined after-tax income for a male and female couple earning average ordinary time earnings, a 10% housing deposit and the average discount variable rate bank mortgage rate for new owner-occupier loans. Since the June quarter 2022, house prices estimates are taken from the monthly Core-Logic house prices series.