7 minutes reading time

It is estimated that as many as 6,500 migrant workers died building the stadiums for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar. The precise number is difficult to estimate, as few workers are afforded autopsies and death from heat stroke is typically recorded as ‘natural causes’1. However, from the moment the first referee’s whistle blew, little attention was paid to the plight of workers, corruption or human rights abuses and all the focus was on the quality of the venues, the experience of the fans, and the success of the tournament:

“As the 2022 World Cup came to a close, Qatar can look back on its journey to prepare for the tournament with pride. The country had overcome significant challenges to deliver an unforgettable event and firmly established itself as a major player in the world of international sports. They have big plans for the future, and their ambitions to change perceptions about the Middle East will allow many more sporting events to take place in the region for decades to come.” -euronews.com, 5 January 20232

Figure 1: Lusail Iconic Stadium Qatar – 6,500 workers died building venues for the 2022 FIFA World Cup

Source: euronews.com

What is sportswashing?

Sportswashing is the practice of countries, companies or organisations using sports sponsorships or partnerships to improve their public image. It is a form of propaganda. By linking themselves to a sporting team, individual or event, governments or companies hope to improve their reputation or distract attention from unethical conduct such as human rights violations, corruption, or environmental vandalism. It is a strategy to seem more virtuous or community-oriented and to buy social licence to operate.

Sportswashing examples

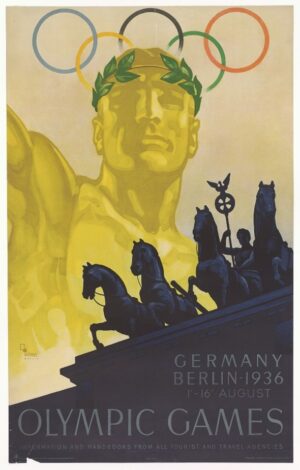

In an early example of sportswashing, Berlin’s 1936 Olympic Games were used by propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels to shift the image of the Nazi Party from that of brown-shirted racist thugs to successful nation-builders and bolster support for Hitler, both domestically and abroad3.

Figure 2: Berlin 1936 Olympic Games Poster

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Recent examples of sportswashing include Qatar’s hosting of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, the Saudi Arabia sponsored LIV Golf Tour, Rwanda’s sponsorship of Arsenal and Paris Saint-Germain, and the same country’s successful bid to host the 2025 Cycling Road World Championships. Shaikh Mansour of Abu Dhabi bought the Manchester City football club and the Saudis own Newcastle United.

Corporate sportswashing had its origins in tobacco company sponsorship of sporting teams and athletes. American baseball greats Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio and Lou Gehrig all appeared in cigarette advertisements as the industry tried to divert attention from emerging health concerns related to tobacco smoking. In the 1980s, tobacco companies were by far the largest sponsors of Australian sport. In 1989 alone, the tobacco industry put $20 million into NSW Rugby League and $14 million into cricket, a huge sum at the time.

Today, much of the focus on sportswashing has switched to fossil fuel companies and companies with high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. BP was a major sponsor of the London Olympics, which was seen by some as an attempt to rehabilitate the company’s image following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Shell is the major sponsor of British Cycling.

Qatar Airlines was a major sponsor of the 2022 FIFA World Cup and is currently a sponsor of some of the world’s biggest soccer teams, including Paris Saint-Germain, Bayern Munich and AS Roma. It heavily promoted the World Cup as carbon neutral, a claim described by climate scientists as “deeply misleading and incredibly dangerous”.4

Figure 3: Qatar Airlines FIFA World Cup Sponsorship

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In Australia, a 2022 study by Swinburne University estimated fossil fuel companies spend up to $18 million a year greenwashing their public image by sponsoring sport5. Woodside sponsors the Fremantle Dockers, Santos sponsors Australian and Queensland Rugby, as well as the cycling Tour Down Under, Hancock Prospecting was a major sponsor of Australian netball and is an ongoing sponsor of the Australian Olympic team, and Alinta Energy has been the major sponsor of Australian cricket.

Why does sportswashing matter?

Sport is big business, and sporting fans can be fanatically loyal. That loyalty can result in a blind eye being turned to important social and environmental issues. During a minute’s applause to show support for Ukraine following Russia’s illegal invasion, Chelsea fans chanted the name of former club owner Roman Abramovich, a Russian oligarch with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin6.

A government that is facing criticism for its human rights record or controversial policies can, by associating with sports and athletes, create a more favourable perception of its actions and policies. The Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) has poured billions into the rebel LIV Golf tour. The objective of the PIF is to implement ‘Vision 2030’, the plan devised by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud to create a diversified and sustainable economy for the country that is not oil-dependent.

Figure 5: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Vision 2030 Promotion

Source: vision2030.gov.sa

To realise that vision, the PIF needs to persuade major companies to come to Saudi Arabia. Sponsorship of LIV Golf gives them access to the world’s biggest corporations and enables them to present a sanitised picture of the kingdom’s leadership. And it seems to have been working.

In 2022, Ritz-Carlton, Hyatt and Rosewood signed mega-deals to develop luxury resorts in the kingdom, while Hilton and Radisson announced plans to build nearly 80 hotels7. Six Flags is building a 90,440-acre theme park and there are plans to develop at least 14 major golf course resorts by 2030.

LIV Golf’s two-year US$2 billion budget is a drop in the ocean compared to the hundreds of billions in foreign investment targeted under Vision 2030. This is all in a country that, according to Human Rights Watch, has carried out the arbitrary arrest, detention and in some cases execution of human rights activists; undertaken airstrikes in Yemen against homes, schools and hospitals, killing thousands of civilians; systematically discriminated against women and girls; and overseen human rights abuses against migrant workers8. A Central Intelligence Agency report concluded that Mohammad bin Salman personally had ordered the assassination of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 20189.

Sportswashing can backfire

Companies that engage in sportswashing can find their attempts to sanitise their image backfire, drawing attention to the very things they were trying to divert attention away from.

In November 2022, a group of Fremantle Dockers fans and former player Dale Kickett signed an open letter to the club, urging them to drop Woodside as a major sponsor. The signatories stated that it was no longer appropriate for the club to be sponsored by a fossil fuel company, as the world is in the midst of a climate crisis driven by companies such as Woodside. Patrick Cummins made similar comments in relation to Alinta Energy’s sponsorship of Australian cricket.

Indigenous netball athlete Donnell Wallam objected to wearing the logo of Hancock Prospecting on her Australian Diamonds uniform in protest against the racist views of company founder Lang Hancock, which included advocating the forced sterilisation of Aboriginal women. Hancock’s daughter and current company executive chair, Gina Reinhart, has never denounced her father’s statements, and subsequently retracted her A$15 million sponsorship of Netball Australia, a contract that was picked up by Tourism Victoria10.

Conclusion

Ethical investors need to be aware of the tactics companies use to divert attention from the negative impacts of their activities. While donations to political parties and the lobbying activities of peak bodies are aimed at influencing the policy environment, sportswashing is a way of exercising ‘soft power’. Sportswashing can alter people’s opinions and make them more favourably disposed towards a company that appears to share their sporting passion. It diverts attention from negative externalities and discourages investors from holding companies to account for their impacts on society or the environment.

Betashares Capital Ltd (ABN 78 139 566 868 AFS Licence 341181) is the issuer of the Betashares funds. Read the Target Market Determination and PDS at www. betashares.com.au and consider with your financial adviser whether the product is appropriate for your circumstances. The value of the units may go down as well as up. The Fund should only be considered as a component of a diversified portfolio.

1. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/les-decodeurs/article/2022/11/15/world-cup-2022-the-difficulty-with-estimating-the-number-of-deaths-on-qatar-construction-sites_6004375_8.html

2. https://www.euronews.com/2023/01/05/fifa-world-cup-qatar-2022-how-qatar-delivered-on-itspromise#:~:text=Despite%20Qatar’s%20challenges%20and%20obstacles,by%20fans%20and%20players%20alike.

3. https://www.npr.org/2008/06/07/91246674/nazi-olympics-tangled-politics-and-sport

4. https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/63466168

5. https://www.acf.org.au/new-research-fossil-fuel-industry-using-sport-to-greenwash-public-image

6. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/dec/24/sport.football

7. https://mygolfspy.com/news-opinion/liv-golf-why-the-saudis-care-so-much-about-golf/

8. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/saudi-arabia

9. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/Assessment-Saudi-Gov-Role-in-JK-Death-20210226v2.pdf

10. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-10-19/sport-money-and-sponsorship-a-complicated-relationship/101552388