7 minutes reading time

- Fixed income, cash & hybrids

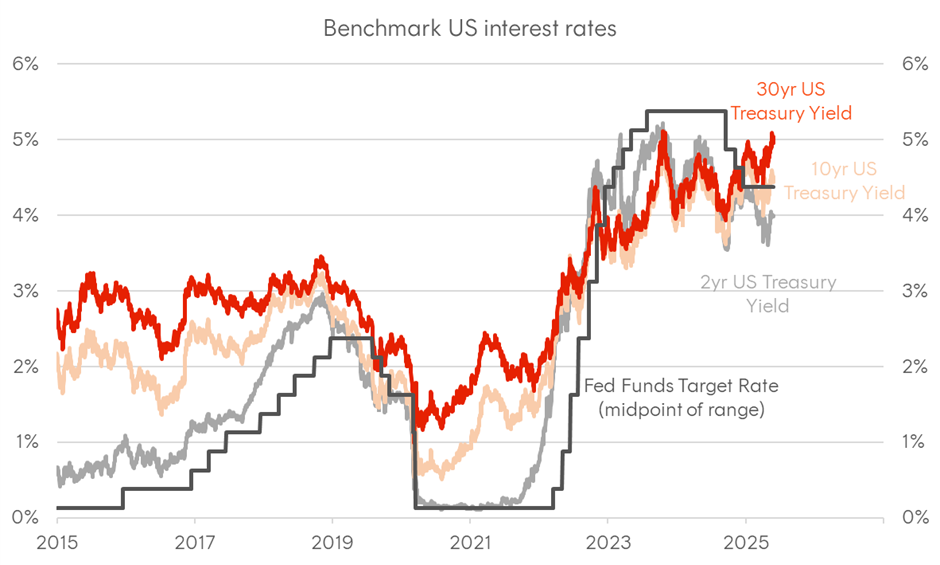

The global bond market doesn’t usually dominate headlines. In recent weeks, however, long-term interest rates on US government bonds have surged past 5%, and this has rattled many investors.

For many Australian investors, it’s easy to tune this out as something distant or irrelevant. However, the reality is US Treasuries is one of the most important markets in the world. Even if you’ve never invested in bonds before, now is the time to understand why they matter and what they’re telling us about the state of the US and global economy.

What has happened?

Ratings agency Moody’s recently stripped the US of its AAA credit rating (joining the two major ratings agencies (S&P and Fitch). Moody’s cited growing concerns about the US government’s budget deficit and debt trajectory under the so-called One Big Beautiful Bill Act (aka “Big Beautiful Bill”) – a sweeping package of tax cuts and spending backed by the Trump administration.

For some investors, this news might sound alarming and a reason to run for cover. Headlines about downgrades and deficits might sound worrying. However, they often also create opportunities. When the world’s benchmark government bonds are yielding 5%, it’s not a time to panic – it’s a time to take notice.

As the following chart shows, long-term investors have historically been rewarded for adding exposure to high-quality government bonds at elevated yields.

Benchmark US interest rates over time

Source: Bloomberg, as at Tuesday 27 May 2025. Yields are subject to change.

What are bonds, really?

“Stocks are stories. Bonds and credit are contracts”

– Torsten Sløk, Chief Economist at Apollo Global Management

At their core, bonds are loans. But unlike your typical loan, many bonds are highly tradeable securities. You lend money to a government or company, and in return, you receive regular interest payments and your principal back at maturity. During the life of the bond, it can be bought or sold in the secondary market.

Australian investors might be familiar with ASX-listed hybrids as a type of tradeable instrument with debt characteristics. But hybrids only scratch the surface of the broader fixed income universe.

What’s often missing from portfolios is exposure to traditional government and corporate bonds, particularly to offshore markets like the US. The US Treasury market is the primary channel through which the US government borrows money. This piece will focus primarily on fixed-rate bonds, which is the largest part of the Treasury market.

Why bonds and the US Treasury market matters

Bonds aren’t just a way for investors to earn income. They’re the very bedrock of global finance. Interest rates on bonds often help set the price of mortgages (especially in the US), corporate borrowing rates and even how investors value shares.

Put another way: bonds often set the price of money.

When interest rates (or “yields”, as they are known for bonds) fall, bond prices rise – especially for longer-term bonds. That’s why many investors use long-term government bonds as a form of portfolio insurance: they have tended to perform well when the economy slows or equity markets fall.

Among all the bond markets in the world, the US Treasury market is most important. US Treasuries are considered the global reserve asset and thought by many to be the global “risk-free rate” – a benchmark against which all other investments are measured.

US Treasuries are also one of the most traded and liquid assets on the planet. They are used by central banks, sovereign wealth funds and everyday Australian investors through their super funds.

When share markets panic, especially amid growth fears, investors often rush into US Treasuries.

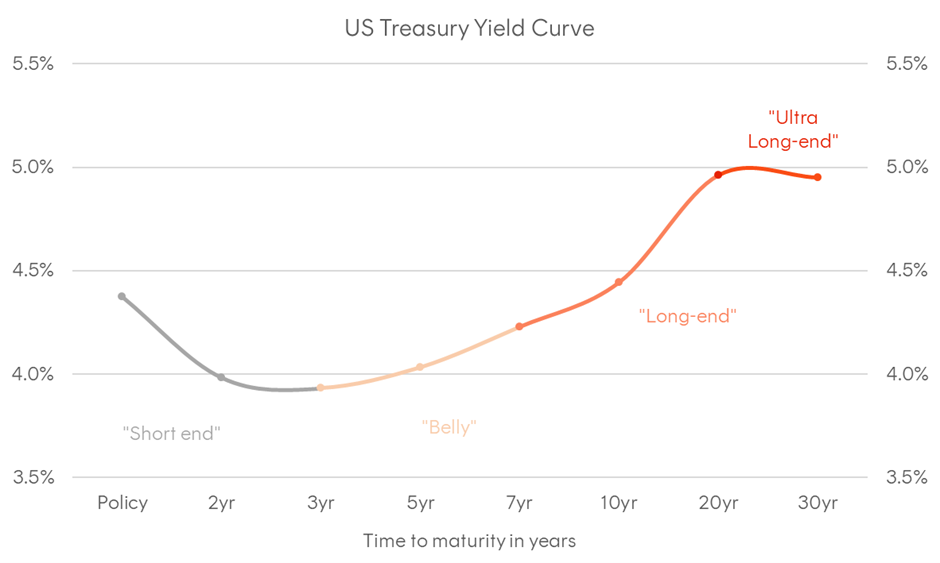

The “curve”, demystified

One of the first concepts you’ll hear in bond investing is “the curve”, which refers to the range of maturities of the bonds in question. It’s typically divided into segments: the short end, the belly, the long end, and the ultra-long end. Although there’s no exact boundary between segments, this is a general guide:

- “Short end”: Bonds between 1 year and 3 years to maturity

- “Belly”: Between 3 years and 7 years to maturity

- “Long end”: Between 7 years and 20 years to maturity

- “Ultra long end”: More than 20 years to maturity

US Treasury Yield Curve

Source: Bloomberg. As at Tuesday 27 May 2025. “Policy” is the current Fed Funds target rate, being an overnight term. Yields are subject to change.

Duration and convexity illustrated

Short-term bond yields tend to move closely with the official policy rate – set by the Federal Reserve in the US, while longer-term yields are shaped more by expectations for future growth and inflation (and by extension, future policy rates). That’s why the yield curve isn’t flat: its shape shifts as the market reassesses the economic outlook. In terms of pricing and valuation, longer-term bonds tend to be more sensitive to yield changes because they have more future cash flows being discounted to today’s value.

This sensitivity is known as duration. Duration is one of the most important concepts in managing bond portfolios.

Shorter-maturity bonds have lower duration and tend to be more stable, as well as the potential to provide a higher yield than cash. Shorter-maturity bonds also tend to track near-term interest rate expectations, simply because interest rates don’t generally change drastically in the short term. In contrast, longer-maturity bonds have higher duration, making them more volatile, but also capable of delivering strong capital gains when rates fall.

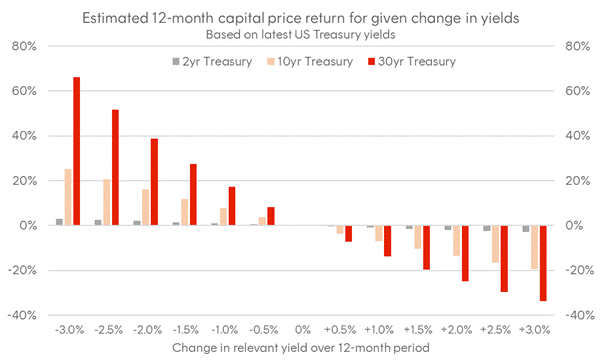

At the ultra-long end, bonds exhibit greater convexity, meaning they typically gain more when yields drop than they lose when yields rise – an attractive trait during market stress, where double digit returns are possible.

Source: Bloomberg. Based on latest US Treasury curve, as at Tuesday 27 May 2025. Estimate for illustrative purposes only.

Implementation ideas: US10 and GGOV

Two ETFs in the Betashares range provide targeted access to different parts of the US Treasury curve:

- US10 U.S. Treasury Bond 7-10 Year Currency Hedged ETF offers exposure to US government bonds with maturities between 7 years and 10 years – what’s typically considered the long-end of the curve.

- GGOV US Treasury Bond 20+ Year Currency Hedged ETF focuses on US Treasuries with maturities beyond 20 years – representing the ultra-long end, where both duration and convexity are the highest.

Both ETFs give investors access to the world’s benchmark asset, but with different levels of price volatility and potential capital upside. US10 aims to strike a balance between yield and rate sensitivity, while GGOV is generally designed for those seeking maximum exposure to moves in long-term interest rates – which could be especially valuable during global economic slowdowns or US recessions.

By contrast, shorter duration ETFs like the recently launched Defined Income series or floating rate ETFs such as the QPON Australian Bank Senior Floating Rate Bond ETF tend to prioritise capital stability and income. These products have limited duration and therefore less sensitivity to benchmark interest rate moves.

Add a solid defence to your portfolio

A well-balanced defensive portfolio can combine floating rate bonds for income stability, shorter-term fixed rate corporate bonds for moderate yield with lower volatility, and longer-term government bonds for protection during market stress and US recessions. With 30-year US Treasury yields still around 5% and a steep yield curve creating some of the most attractive starting points in years, it’s a moment that demands attention.

[1] https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/05/ltbondrisk.asp