3 minutes reading time

At face value, today’s first fully complete monthly CPI report does little to ease fears that the lift in inflationary pressures evident in the September quarter will quickly subside.

Given that most of the individual CPI components are not seasonally adjusted, it is difficult to make much sense at this stage of their recent month to month movements.

What we do have, however, is the seasonally adjusted trimmed mean measure of overall underlying inflation – which suggests little easing in price pressures in October.

The trimmed mean lifted by 0.33% in the month, compared with slightly smaller gains of 0.27% in both September and August. Over the year, trimmed mean inflation edged up to 3.3% from 3.2% in September. Annual trimmed mean inflation has been edging gradually higher since its low of 2.8% in June. So far, so bad.

Although widely reported, it’s worth remembering that the annual inflation measure (i.e. the price increase over the past 12 months) is to a degree backward looking, as it reflects both recent price changes and those that took place up to a year earlier.

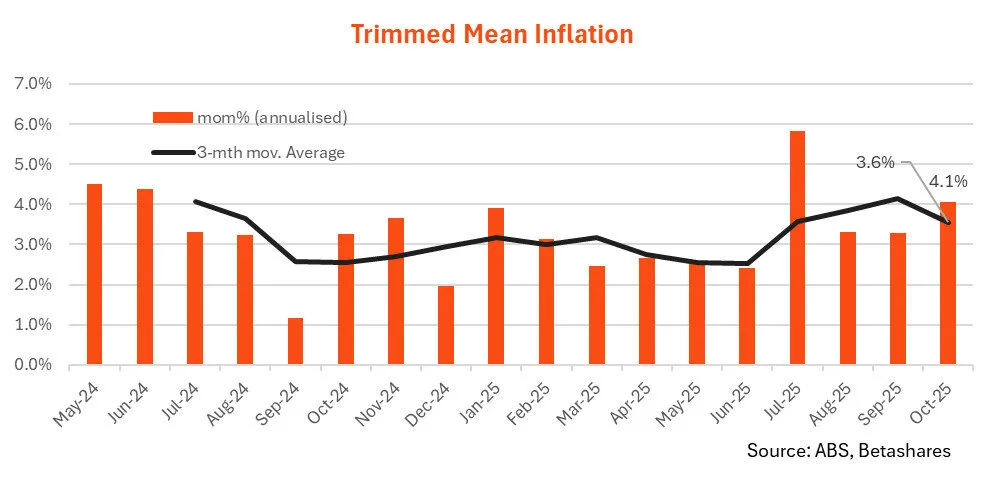

Indeed, as the RBA recently noted, annual measures of trimmed mean inflation are likely to remain elevated for some time due to the relatively large price gain in the September quarter. Indeed, the new monthly CPI report reveals that trimmed mean inflation rose by an unusually large 0.47% in July, or a 5.8% annualised rate.

What matters for the Reserve Bank and the interest rate outlook going forward, therefore, is not the annual rate of underlying inflation per se, but what can be gleaned from more recent monthly trends.

On this score, the early omens are not great.

As evident in the chart below, the 0.33% monthly gain in the trimmed mean price measure implies an annualised inflation rate of 4.1%, which is still comfortably above the RBA’s 2 to 3% target band. Taking the average annualised monthly change over the past three months – to smooth out monthly volatility – annualised inflation did ease from 4.1% to 3.6% in October. Although this is an encouraging drop, however, it is still comfortably above the RBA’s 2 to 3% target band.

Barring a major slump in economic growth and/or rise in unemployment, for the RBA to contemplate cutting interest rates next year we’ll need to see the annualised rate of monthly inflation dip convincingly below 3%.

What’s more, unless inflation does convincingly drop to this level, there’s a risk the RBA will instead have to consider higher rates in 2026. This is on the view that the economy is still operating at an overly high level of capacity which is creating lingering inflationary pressure.

My base case is that inflation will ease in coming months, on the view that some of the recent price gains have been one-off price level adjustments – or rebuilding of profit margins – as both consumer spending and housing demand has recovered. But even under this scenario, it’s hard to see the RBA having sufficient evidence to justify a rate cut before May. I also do acknowledge, however, my benign inflation view could turn out wrong, meaning higher rates next year can’t yet be ruled out.