8 minutes reading time

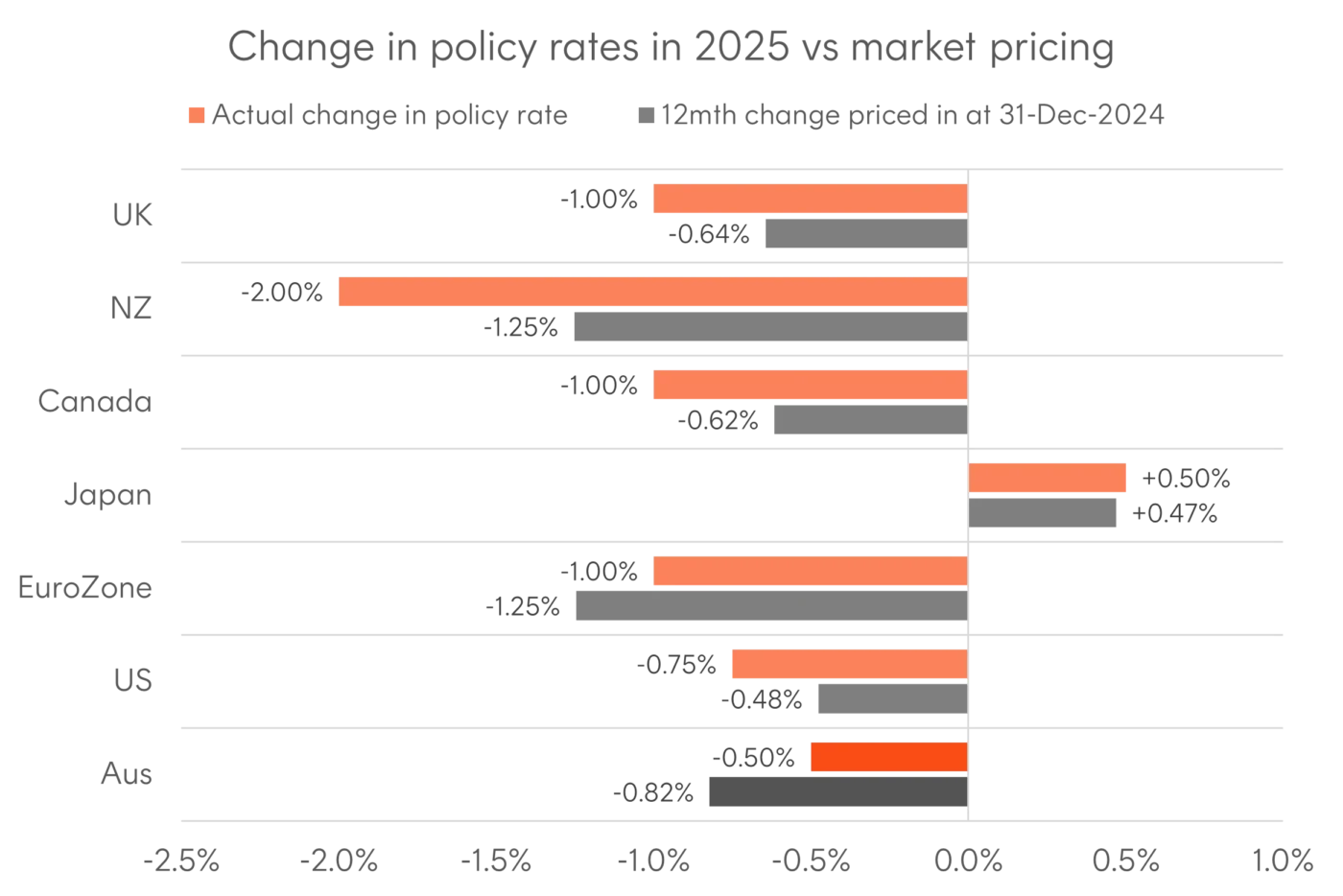

Markets began 2025 pricing in a globally synchronised easing cycle and central banks largely delivered on those expectations. The Fed, European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of England (BoE), Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), and Bank of Canada (BoC) all made several rate cuts during the year, while the RBA delivered three 25 basis point cuts of its own, taking the cash rate from 4.35% to 3.60% by the mid-year. The notable exception was the Bank of Japan (BoJ), which continued to gradually normalise policy after decades of ultra-loose settings.

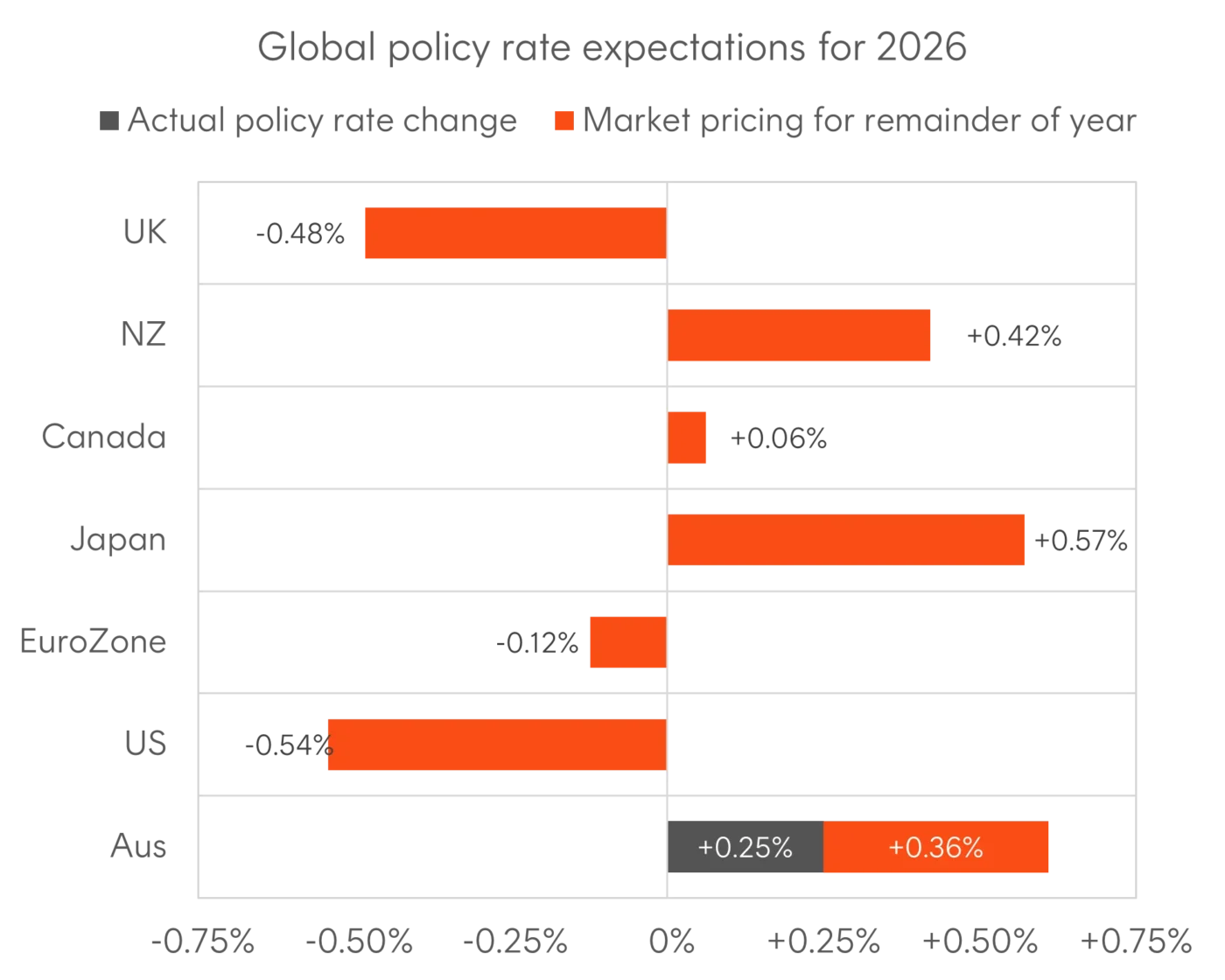

However, divergence started to emerge as a theme in the latter part of last year. As inflation proved stickier than expected in several economies, markets began repricing the outlook for policy. By year-end, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand were all expected to join the BoJ in adopting a tightening bias. The RBA was first to act in the new year, raising the cash rate by 25 basis points to 3.85% at its February meeting.

In contrast, the Fed has maintained dovish guidance, and along with the BoE, the most dovish among the major central banks. A relatively dovish Fed, and rate cuts alongside rate hikes from other central banks could have significant implications for both global rates and currencies.

Figure 1: Change in policy rates in 2025 and market pricing at the start of the year

Sources: Bloomberg, ASX, CME, RBA, RBNZ, Fed, BoC, BoJ, ECB. As at 31 December 2025.

Figure 2: Policy rate expectations for 2026

Sources: Bloomberg, ASX, CME, RBA, RBNZ, Fed, BoC, BoJ, ECB. As at 6 February 2026.

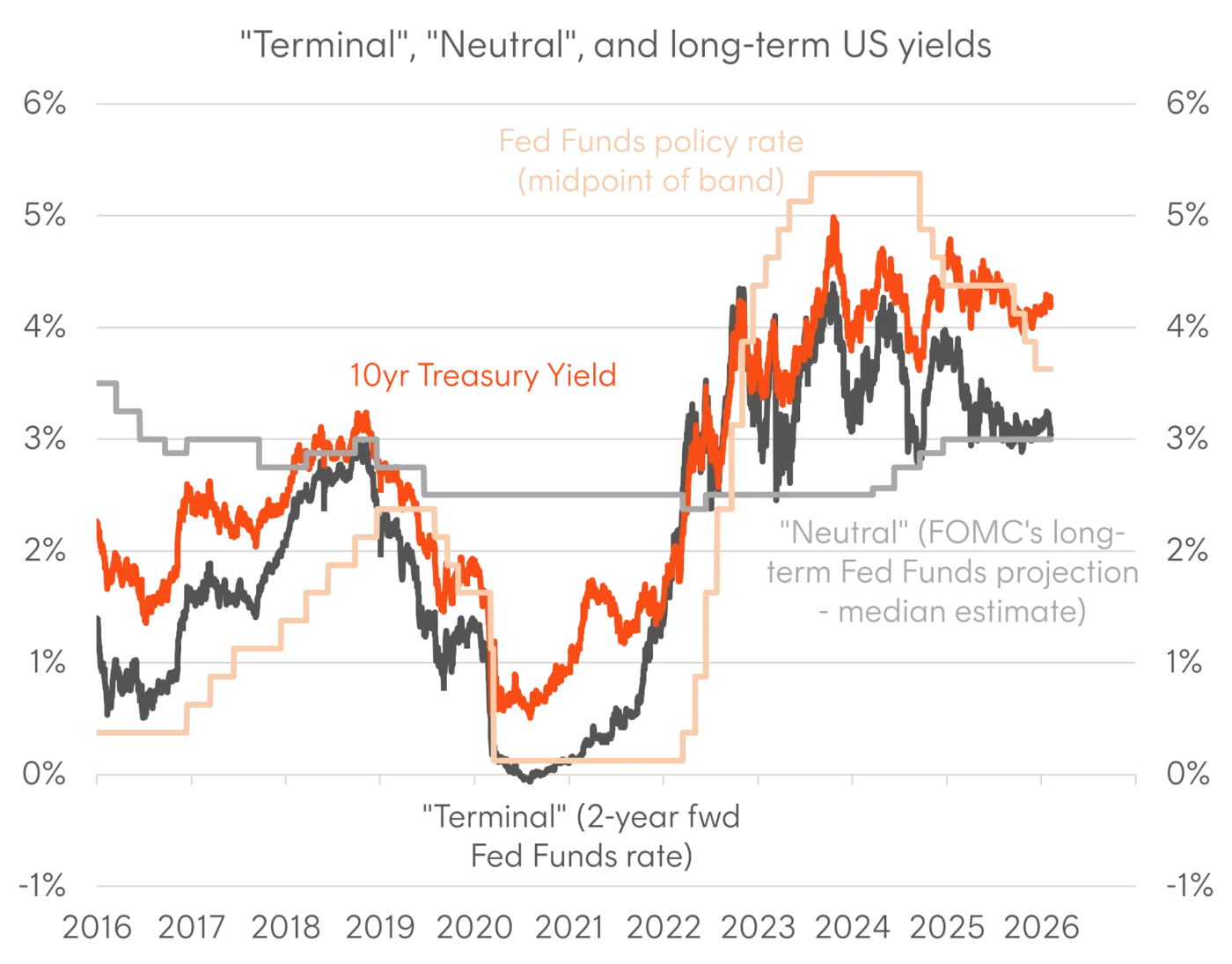

Signals from the US bond market

Despite the political noise and policy uncertainty from Washington, the US fixed income market is currently presenting a constructive picture for US growth in 2026. Interest rate volatility remains low, including forward looking measures. The US yield curve is gradually steepening, which is consistent with a Fed easing cycle continuing. Credit spreads remain tight, suggesting the market isn’t pricing in meaningful recession risk.

Figure 3: Selected US interest rates

Sources: Fed, Bloomberg, CME. As at 6 February 2026.

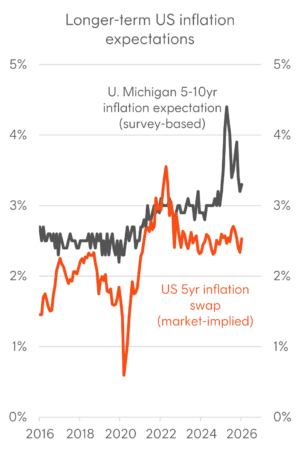

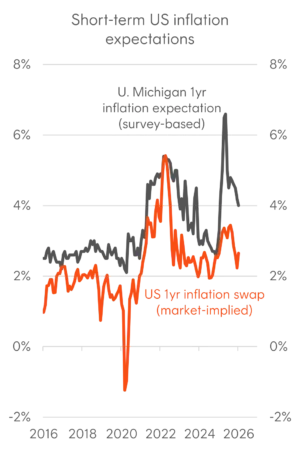

In addition, market-implied inflation expectations are still largely anchored. Inflation is likely to remain above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target but gradually trend lower over the year on waning tariff effects. Upside risks to inflation include delayed pass through from businesses, renewed tariff shocks, supply chain reshoring, and energy price volatility either from increasing AI electricity demand or a geopolitical event. Taken together, this is an outlook consistent with at or above-trend growth, with inflation pressures broadly under control.

Figure 4: US inflation expectations

Source: Bloomberg. As at 31 January 2026.

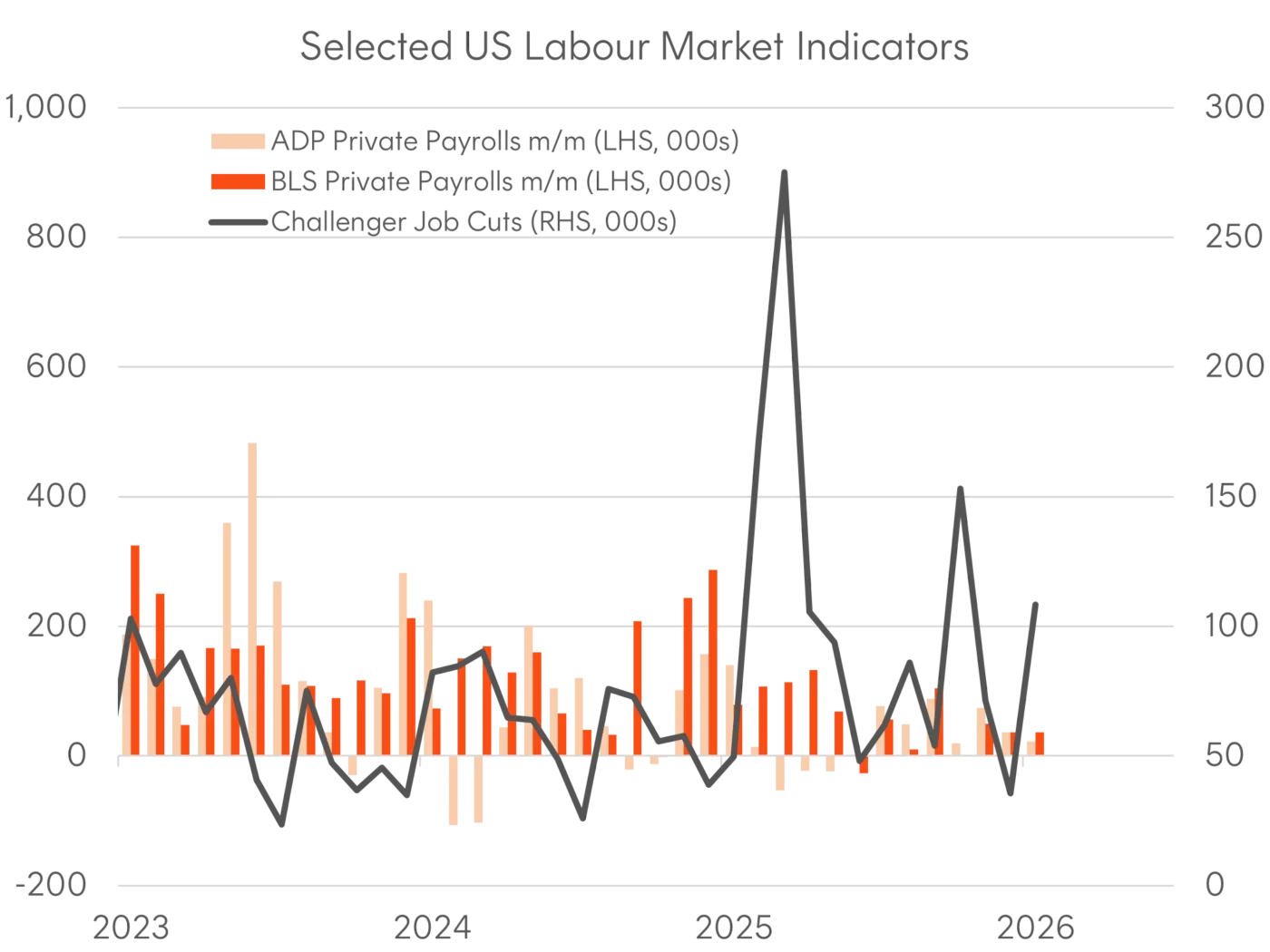

The key risk remains the labour market, and the US Treasury market remains highly attuned to weaker than expected jobs data. Despite fiscal support, an AI capex boom, and strong corporate profitability, the US labour market deteriorated over the course of 2025 and remains soft based on early 2026 data releases. With job creation stalling, the unemployment rate trended higher last year, from 4.1% to 4.4%. Restrictive immigration policy has also weighed on labour supply at the margin, and the breakeven job creation rate may have structurally declined from around 150,000 a month to closer to 50,000.

Importantly, a low-hiring environment can be sustained with limited knock-on effects, provided layoffs don’t accelerate. But if unemployment continues to climb in 2026, genuine recessionary risks would force the Fed to cut rates further and take policy to accommodative levels. AI may have a role to play in this labour market story. Lower job creation could be a function of higher productivity as corporates look for efficiency gains from AI, but this could turn to layoffs if profit margins come under threat.

Figure 5: Selected US Labour Market Indicators

Sources: BLS, ADP, Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

A captive Fed?

The Trump Administration has frequently attacked the FOMC and Chair Powell for not cutting rates aggressively enough, and Fed independence was a recurring theme for markets throughout 2025. “Fiscal dominance” – where a central bank works in service of fiscal policy by keeping rates lower than they should otherwise be – remains a risk in an environment where the Administration favours expansionary fiscal policies to support nominal growth.

On 30 January, Trump nominated Kevin Warsh to succeed Powell when his term ends in May. The nomination has gone some way to soothing fears around the loss of Fed independence. Warsh is a known quantity, having previously served as a Federal Reserve Governor from 2006 to 2011. His track record suggests he has historically leaned hawkish but more recently, he has indicated support for further rate cuts, driven by a view that AI-led productivity gains could boost growth without stoking inflation. He has also remained critical of the Fed’s reliance on quantitative easing and forward guidance, and it’s possible we’ll see a continuation of the rate cutting cycle coinciding with a shrinking balance sheet under his watch.

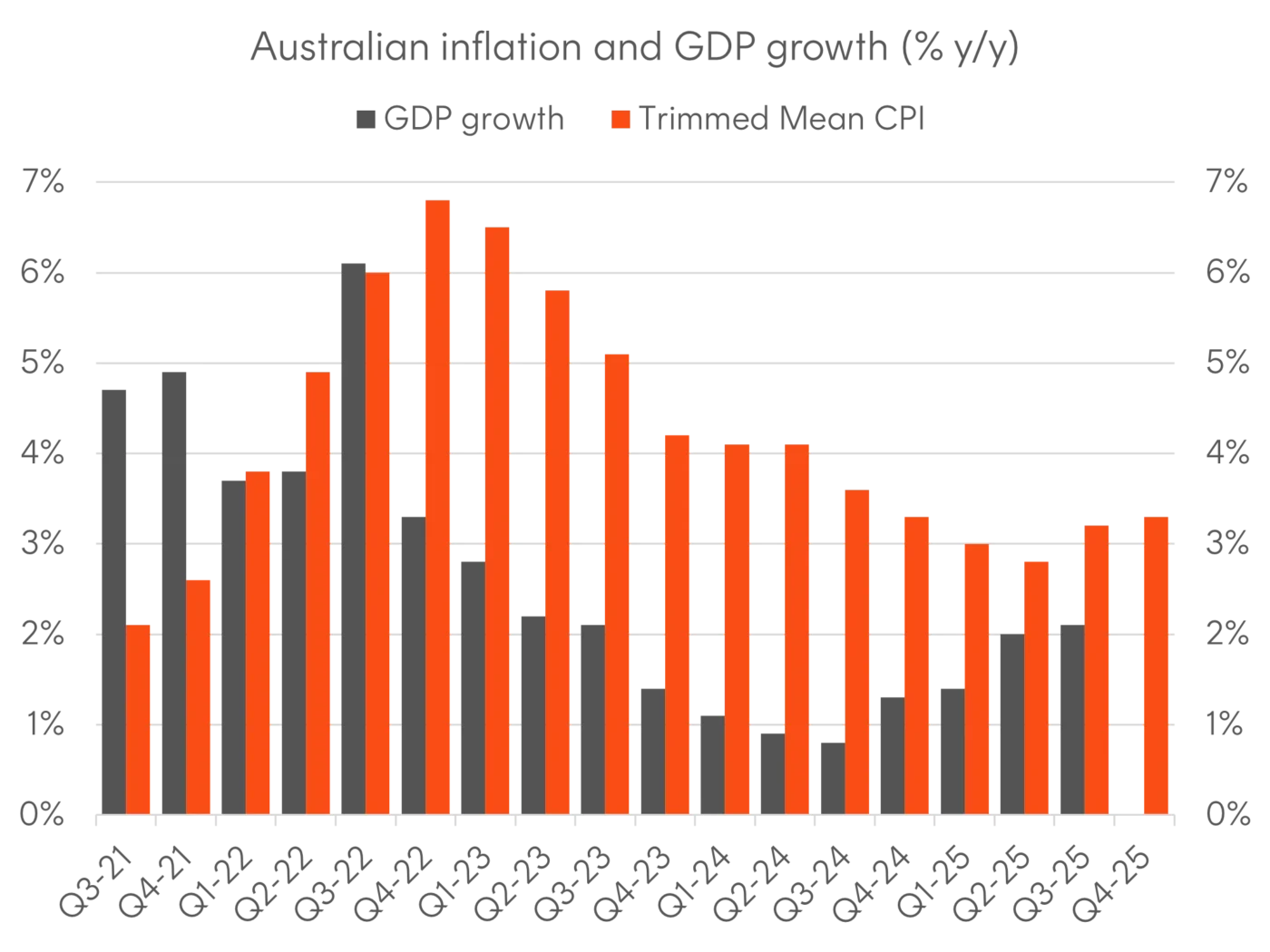

Australia’s inflationary constraints, risk or reward?

The Australian economy faced a reality check of sorts late in the year. Disappointingly, the lift in economic growth was also associated with a bounce back in inflation. Trimmed mean quarterly inflation lifted by 1.0% in the September quarter and eased to only 0.9% in the December quarter. As a result, annual trimmed mean inflation ended 2025 at 3.3% – a notable rebound from the June quarter low.

Figure 6: Australian GDP Growth and Trimmed-Mean CPI

Source: ABS. GDP data as at 30 September 2025 and CPI data as at 31 December 2025.

What’s more, demand factors appear to account for a good degree of the lift in inflation, with new home costs and rents rising notably. Pricing pressures were also evident in the travel and hospitality sector although, at least in the December quarter, and an element of this likely reflected “one-off” added tourism demand related to the Ashes cricket series.

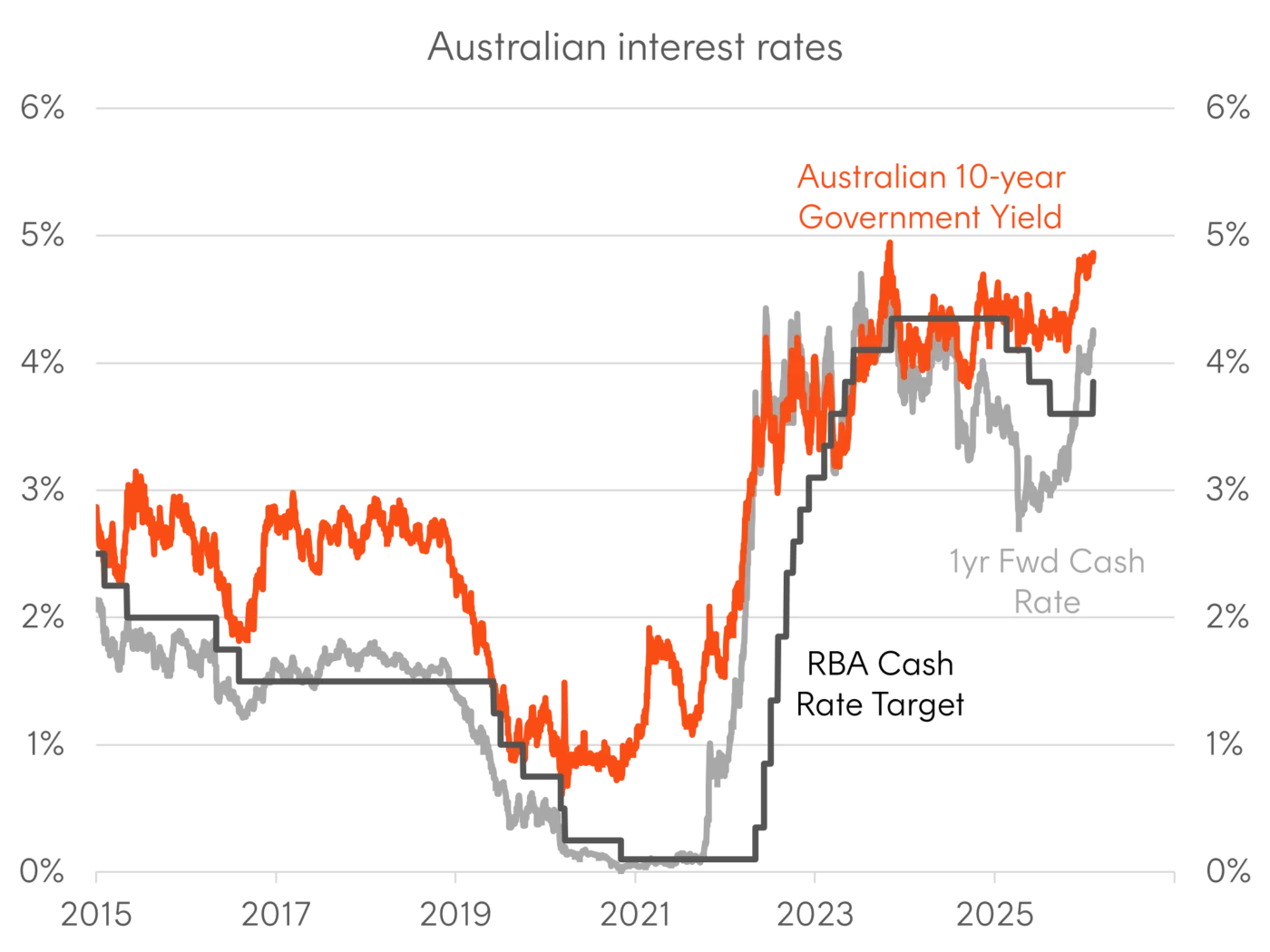

Reflecting the rebound in inflation, the RBA delivered on expectations by raising the cash rate target by 25 basis points at the February meeting. Our base case, however, is this will be a very modest hiking cycle, with potentially only one or two further hikes as the Bank attempts to recalibrate to a “neutral” policy setting. The evolution of inflation remains key to the outlook, and fortunately the official series is now monthly, which should present a timelier read for cash rate expectations. However, another factor in the policy outlook are global developments, and if a US or global growth scare were to emerge, it’s likely we’ll see rate hike expectations unwound.

We don’t expect the magnitude of recent underlying price increases to be sustained, in part because some of the increase also likely reflect temporary factors, such as a lift in global food prices, a reduction in discounts that had been temporarily offered by home builders, and Ashes related tourism spending. We also anticipate a degree of competitive pressure on profit margins and only modest consumer spending – especially given tighter monetary conditions – to limit underlying price pressure in 2026.

As for Australian fixed income, it’s important to remember that markets are forward-looking and while a hiking cycle might at first seem challenging for fixed-rate bonds, the historical evidence suggests otherwise. With rate hike expectations already embedded in yields, in addition to an attractive term premium further out the curve (with 10-year yields well above “terminal” rate expectations from cash rate futures) and elevated starting yields, there’s arguably a favourable risk-return asymmetry in long-term high-grade bonds currently.

For investment implications, read why we believe Australian bonds stand out as the best risk adjusted return opportunity for core fixed income allocations.

Figure 7: Selected Australian Interest Rates

Sources: Bloomberg, RBA, ASX.