5 minutes reading time

On paper, Australia’s economy continues to exhibit resilience.

On a pure GDP growth basis, Australia has not had a deep recession since the early 1990s and the economy continues to grow modestly. In October 2025, the Australian unemployment rate was 4.3% (it’s not been above 5% since 2021) and the participation rate, or percentage of Australians able and looking for a job, remains healthy. Permanent and long-term migration also topped 400,000 over the first nine months of 2025, a record inflow that should support consumption demand.

Yet as 2025 draws to a close, the streets tell a different story.

Walk through many shopping precincts and the difference becomes apparent. Foot traffic remains steady but shopping bags are scarcer than they used to be. A Fitness First spruiker on Sydney’s George Street was recently offering nine weeks free – far more than the four weeks it has offered in the past. Calvin Klein and The Iconic (among others) started Black Friday sales weeks early. The ABS noticed this trend last year and, so far, 2025 only intensified it.

So which one is right?

The answer is: they both are, but they’re telling the story of different moments in time. Australia saw a real disconnect between economic data, consumer sentiment and polling between 2022 and 2024. But by late 2025 the economy began to shift as the reality started catching up to the vibe. Despite continued street caution, consumer confidence reached its highest point in almost four years. This discrepancy between the economy’s performance and sentiment highlights an important point for investors: sentiment follows economic turning points, frequently by months or even years, rather than predicting them.

What is the ‘vibecession’?

The term vibecession was coined by American economic commentator Kyla Scanlon in 2022 to describe a strange situation: when the economic feeling is bad but the data is good. It’s not a real recession but it feels like one.

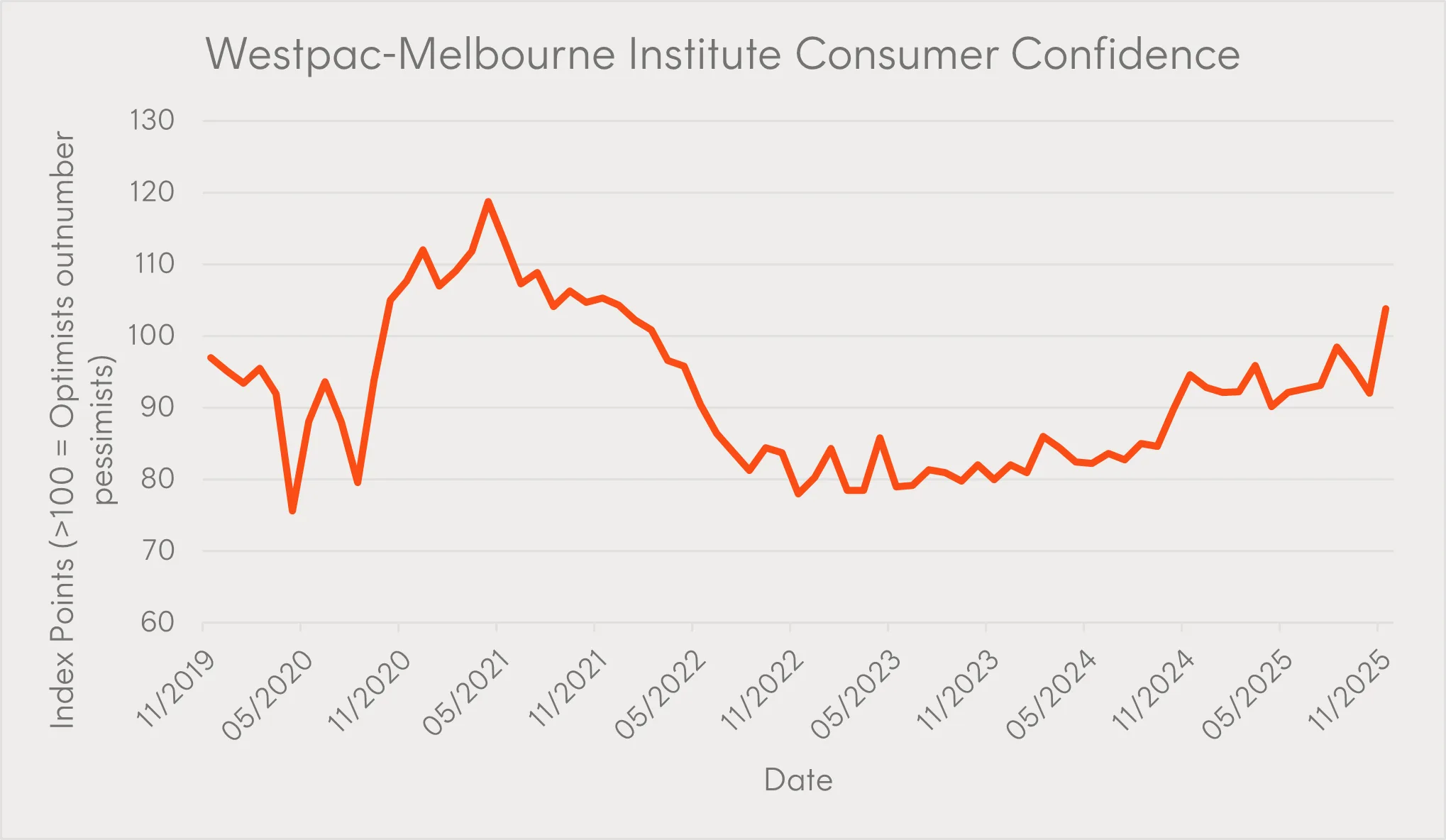

Consumer sentiment in Australia tells this story in two acts. Through 2022-2024 Australia experienced a textbook vibecession: sentiment dropped below 100 (the neutral threshold where the number of optimists equal the number of pessimists) even as unemployment remained low and GDP growth continued. But November 2025 marked a turning point: the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Index surged to 103.8, the first time that optimists had outnumbered pessimists since February 2022.

This wasn’t just improvement. It was a breakthrough to seven-year highs, excluding the COVID period. The vibecession, it seems, is ending in Australia. Sentiment isn’t predicting where the economy is going; it’s finally catching up to where the economy has been.

Source: AFR, Westpac-Melbourne Institute. Note: November 2025 data shows sentiment breaking above 100 for the first time since early 2022.

How we contrast with the US

While Australian sentiment has normalised, America’s ‘vibecession’ persists. US consumer confidence, as per The Conference Board’s survey, sat at 88.7 in November 2025. This is well below the historical average and beneath the 101.9 level that typically marks the start of recessions. Despite robust GDP growth driven by an AI construction boom, American consumers remain pessimistic.

The difference matters: Australia’s vibecession was a temporary psychological adjustment to higher prices that eventually normalised as wage growth recovered and inflation cooled. In contrast, America’s experience reflects something deeper: entrenched income inequality between asset-rich and working-class households.

Why does the lived experience feel so different?

The story of the last five years falls into two chapters. From 2020 to mid-2024 Australian households endured a squeeze: home prices rose 19.8% nationally, with essentials hit hardest. During this period, real wages – the purchasing power of what workers actually earn – fell sharply as inflation outpaced wage growth.

But the second chapter, from mid-2024 to late 2025, tells a different story. Real wages have now grown for seven consecutive quarters, with annual growth recently hitting the strongest pace since June 2020.

But there is a catch. Despite seven quarters of recovery, the average Australian worker’s purchasing power remains around 4-5% below pre-pandemic levels. Put simply, households remember the ground they lost, even if the economic data shows improvement.

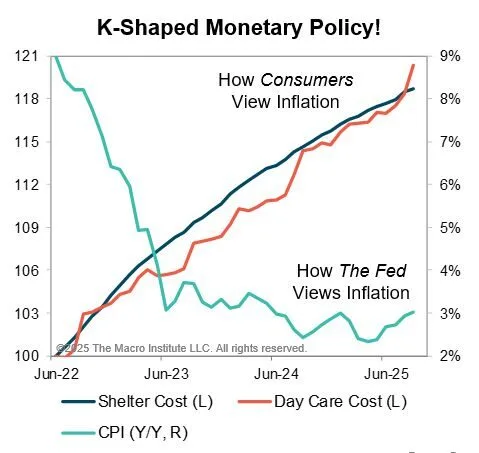

Economists call this a K-shaped recovery. In the US, it’s income inequality: assets versus wages. In Australia, it’s interest rates: mortgage holders crushed by payment increases while retirees benefit from higher savings rates. Central banks celebrate inflation returning to target, but consumers feel the cumulative price increases.

Source: Francois Trahan, The Macro Institute

What’s kept GDP growth resilient in both countries despite consumer caution? In the US it’s the AI construction boom and in Australia the ‘care economy’, robust government spending on healthcare, aged care and the NDIS. These non-consumer sources of growth explain why headline economic data has remained solid even as household spending patterns shifted. Markets that focused only on consumer sentiment missed these alternative growth engines.

For investors, this divergence is the story

The vibecession was real – just not in the way most people thought. Sometimes consumer sentiment leads the data. Sometimes it lags it. The trick is figuring out which phase you’re in, because waiting for perfect alignment between the two means you’re probably already late.